Woman Suffrage Movement

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State on account of sex”–Nineteenth Amendment, U.S. Constitution.

In August 1920 the Tennessee General Assembly ratified the Nineteenth Amendment and handed the ballot to millions of American women. The amendment’s jubilant supporters dubbed Tennessee “the perfect 36” because, as the thirty-sixth of the forty-eight states to approve the amendment, it rounded out the three-fourths majority required to amend the Constitution. The legislature’s historic vote inaugurated a new era for women and for politics and secured Tennessee’s place in the annals of American women’s history.

Tennessee became the final battleground in a struggle that began in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. The demand for the vote was the most controversial of the twelve resolutions adopted at the first women’s rights convention in the United States and the only one that did not win unanimous approval. Suffrage seemed like such an outlandish idea at the time that it made feminists easy targets for ridicule. Still, women like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony persisted and made the vote the focal point of the crusade for women’s rights.

Suffragists (as the advocates of votes for women were called) faced stiff opposition, especially in the South. Long after the Civil War, many southerners continued to remember that feminism had emerged as an offshoot of abolitionism. More importantly, the call for women’s rights challenged a precept deeply rooted in religion, law, and custom: the belief that women should be subordinate to men.

But in the South as in the North, some women resented their inferior status and joined the quest for suffrage. Elizabeth Avery Meriwether of Memphis was among the first. In the early 1870s she wrote letters to newspapers and briefly published her own journal to promote women’s rights and prohibition. Meriwether attempted to cast a ballot in the 1876 presidential election, then rented a theater to explain why she believed women should have the right to vote.

After Elizabeth Meriwether left Tennessee in 1883, her sister-in-law Lide Meriwether took up the cause. Lide Meriwether served as president of the state Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) for the next seventeen years and until her retirement in 1900 led the fight against liquor and for women’s rights. The WCTU played a central role in the debate over the hotly contested issue of prohibition: Union members lobbied the state legislature, circulated petitions, and held prayer meetings at polling places where referenda outlawing liquor were on the ballot. As a result of the temperance crusade, many women became convinced that they had a place in politics, and under Meriwether’s leadership the WCTU endorsed woman suffrage.

Meriwether founded Tennessee’s first woman suffrage organization in Memphis in 1889. The second appeared in Maryville in 1893; the third, in Nashville a year later. By 1897, the year of the Centennial Celebration in Nashville, ten towns had suffrage societies. Suffragists met at the Exposition’s Woman’s Building in May, heard speeches by suffrage leaders from Kentucky and Alabama, and formed a state association with Meriwether as president.

The state organization held its second meeting in Memphis in 1900, and Meriwether announced her resignation. She had been the driving force for suffrage since the mid-1880s, and her retirement was a severe blow to the struggling movement. The cause received another blow when the WCTU, under new leadership, renounced its earlier endorsement of votes for women. Prohibition had gained public support, but woman suffrage remained unpopular. The temperance union sacrificed women’s rights for the sake of its larger goal. After 1900 suffrage activity ceased for several years.

The movement revived in 1906, when southern suffragists met in Memphis to form a regional association. During the conference, Memphis women organized their own suffrage league, the only one in the state for the next four years. In 1910 Lizzie Crozier French, who, like Lide Meriwether, had campaigned for suffrage and temperance since the 1880s, founded a suffrage society in Knoxville. The following year, women in Nashville, Chattanooga, and Morristown established local organizations. Over the next several years, suffrage clubs appeared in towns throughout the state.

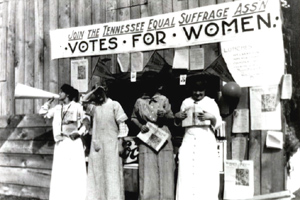

In 1913 Sara Barnwell Elliott, president of the Tennessee Equal Suffrage Association, invited the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) to hold its next convention in Tennessee. NAWSA officers accepted the invitation and asked the state organization to decide which city would host the convention. A poll of local leagues produced a tie between Chattanooga and Nashville. At an acrimonious meeting the state executive committee selected Nashville, but the dispute led to a rift in the association, and the state convention in Knoxville during October 1914 split into two factions. Meeting on opposite ends of the same hall, one group elected Lizzie Crozier French president while the other chose Eleanore McCormack of Memphis. Each claimed to be the original organization, and each side blamed the other for the rupture. French’s group obtained a charter as the Tennessee Equal Suffrage Association, Incorporated (TESA, Inc.). McCormack’s faction also called itself the Tennessee Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) but did not incorporate.

Both associations affiliated with NAWSA, but TESA, Inc. welcomed the national convention to Nashville in November 1914. The meeting brought some of the most famous women in the nation to Tennessee, including reformer Jane Addams, founder of Hull House in Chicago, and NAWSA president Anna Howard Shaw, a physician and ordained minister. In addition to business meetings, suffragists also hosted such social events as a barbecue at the Hermitage that featured a race between an automobile with a female driver and an airplane with a female pilot. The convention attracted favorable publicity and increased support for suffrage in Tennessee.

The two state suffrage organizations offered separate proposals to enfranchise women. TESA, Inc., lobbied for an amendment to the state constitution. In May 1915 the general assembly adopted a joint resolution favoring the proposal, the first step in the amendment process. The resolution would have to pass again in 1917 and then be approved by a majority of voters before it could become law. Because the procedure for amending the constitution was so cumbersome, TESA joined with other groups, including the Manufacturers’ Association, in calling for a convention to draft a new constitution that would, suffragists hoped, allow women to vote. The disagreement over strategy and TESA’s alliance with the Manufacturers’ Association, which opposed many reforms suffragists favored, widened the rift between the two state organizations.

A third statewide suffrage organization appeared in Tennessee in 1916 when Knoxville women formed a branch of the Congressional Union (later renamed the National Woman’s Party). The union represented the militant wing of the suffrage movement and never gained a large following. State chair Sue Shelton White, however, attracted national attention in 1919 when she and other radical suffragists were arrested for burning President Woodrow Wilson in effigy during a demonstration in Washington, D.C.

Opponents of suffrage–antisuffragists or antis–also organized in 1916, forming a branch of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. Virginia Vertrees of Nashville became the group’s first president. When ill health forced her to resign, Josephine Anderson Pearson of Monteagle replaced her. Smaller than the suffrage organizations, the association nevertheless became a potent force because it received support from some of the most powerful political lobbies in Tennessee, including distillers, textile manufacturers, and railroad companies. Virginia Vertrees’s husband John, a Nashville attorney who represented a major distillery, directed the association from behind the scenes.

Suffragists and antis faced off in 1917 when the general assembly considered a proposal to grant women the right to vote in local elections and for president. Suffragists lobbied hard for the bill; antis worked equally diligently against it. Suffragists won a major battle but lost the war when the House passed the measure but the Senate defeated it. Suffragists then resorted to another tactic. Before the session adjourned, both TESA and TESA, Inc., renewed the call for a constitutional convention. Antis mobilized a counterattack. Convinced that a majority of men opposed votes for women, John Vertrees and others maneuvered for a referendum on woman suffrage. They hoped that a decisive defeat at the polls would put the issue to rest. The legislature refused to approve the referendum, but lawmakers scheduled an election on a constitutional convention for July. On July 28, 1917, voters overwhelmingly rejected the proposal.

A few months earlier, in April 1917, the United States had entered World War I. Suffragists threw themselves into the war effort. They sold war bonds, organized Red Cross chapters, planted “Victory Gardens,” and raised money to support European orphans and provide luxuries to American soldiers overseas. The war gave suffragists the opportunity to demonstrate their patriotism and to counter the argument that women should not be allowed to vote because they could not contribute to national defense.

In 1918 TESA and TESA, Inc., reunited, and the following year they once again lobbied the general assembly for the right to vote in municipal and presidential elections. This time they succeeded; both houses passed the bill in April. John Vertrees immediately filed a lawsuit challenging its constitutionality, but the Tennessee Supreme Court upheld the law. Tennessee suffragists had won their first major victory.

Two months after Tennessee granted women partial suffrage, Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment. By the spring of 1920, thirty-five states had ratified it. If one more state approved it, women might be enfranchised in time to vote in the fall elections. When the Delaware legislature unexpectedly defeated the amendment in early June, suffragists pinned their hopes on Tennessee. They knew that they faced a difficult struggle. Although suffrage had gained popular support, strong opposition remained. Before debate on the amendment could begin, suffragists had to persuade the governor to call a special session of the legislature. Governor Albert H. Roberts had spoken against woman suffrage during his campaign two years earlier. He belonged to the antiprohibition wing of the Democratic Party, and his closest advisers opposed votes for women. He feared that women would vote against him because of his opposition to women’s rights and prohibition and because of persistent rumors about his relationship with his highly paid female personal secretary. Roberts faced a tough race for reelection in 1920, and he knew that woman suffrage might bring about his downfall.

Suffragists and their allies mobilized. Sue Shelton White wrote the governor a letter on behalf of the National Woman’s Party, and TESA sent a delegation of prominent women to meet with him. Both organizations enlisted pro-suffrage politicians and officeholders, including President Woodrow Wilson. Finally, the governor capitulated. On June 25, 1920, he announced that he would convene the general assembly in August. The governor’s announcement set off one of the most heated political battles in Tennessee history. Suffragists and antisuffragists alike converged on Nashville; each side was determined to win the final battle.

Anne Dallas Dudley, Catherine Talty Kenny, and Abby Crawford Milton led the fight for the amendment. All three were leaders in TESA and in the newly formed League of Women Voters, and all were veterans of several legislative campaigns. They were skilled politicians, well versed in the realities of Tennessee politics. They received extensive support from the national suffrage organization. NAWSA President Carrie Chapman Catt coordinated the early stages of the campaign from New York. In mid-July she came to Nashville and remained until the fight was over. The National Woman’s Party sent Sue Shelton White and South Carolinian Anita Pollitzer to lobby for the amendment.

The antis criticized the suffragists for inviting outsiders into Tennessee, but they called in their own reinforcements, including the wife of a former Louisiana governor and the presidents of the Southern Women’s League for the Rejection of the Susan B. Anthony Amendment and the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. They also received assistance from three prominent southern women–Laura Clay of Kentucky and Jean and Kate Gordon of Louisiana–who favored votes for women but opposed the federal amendment because of their commitment to states’ rights. Antisuffragists established their headquarters in the Hermitage Hotel and launched a massive publicity campaign.

Both sides recruited male allies–including newspaper editors, businessmen, and politicians–and courted legislators. Suffragists repeatedly accused antis of using underhanded tactics. Early in the summer, TESA polled members of the general assembly and identified lawmakers who promised to vote for the amendment but who might be susceptible to bribes. By August, every single legislator listed as susceptible had defected to the antis.

The special session convened on August 9. The Senate was solidly pro-suffrage and ratified the amendment four days later. The House delayed. Speaker of the House Seth Walker, who had originally supported the amendment, changed his mind on the eve of the session’s opening and used his power to postpone the vote. The House debated the amendment on August 17 and scheduled the vote for the following day. The galleries were packed when Walker called the session to order on August 18. In the tense atmosphere, both sides knew the vote was too close to call. A motion to table the ratification resolution ended in a tie which represented a victory for suffragists, although the real test lay ahead.

The roll call began. Two votes for were followed by four votes against. The seventh name on the list was Harry Burn, a Republican from McMinn County. Suffrage polls listed him as undecided. He had voted with the antis on the motion to table, and suffragists knew that political leaders in his home district opposed woman suffrage. They did not know, however, that in his pocket he carried a letter from his widowed mother urging him to vote for ratification. When his name was called, Harry Burn voted yes.

Suffragists also received unexpected support from Banks Turner, an antisuffrage Democrat who at the last minute bowed to pressure from party leaders, and from Seth Walker, who at the end of the roll call switched his vote from no to aye. Walker’s reversal did not reflect a change of heart. It was, instead, the first step in a parliamentary maneuver that would enable the House to reconsider the ratification resolution. But when Walker changed his vote, he inadvertently gave the amendment a constitutional majority; the final tally showed that fifty of the ninety-nine House members had voted yes. Tennessee had ratified the Nineteenth Amendment. During the next several days antisuffrage legislators attempted to rescind Tennessee’s ratification, but their efforts failed. On August 26, 1920, Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby issued a proclamation declaring the Nineteenth Amendment ratified and part of the United States Constitution.

Tennessee suffragists were elated and proud of the pivotal role their state had played. “I shall never be as thrilled by the turn of any event as I was at that moment when the roll call that settled the citizenship of American women was heard,” Abby Crawford Milton wrote. “Personally, I had rather have had a share in the battle for woman suffrage than any other world event.” (1) The victory was especially sweet because of the deeply entrenched hostility that suffragists faced in the South; only three other southern states–Arkansas, Kentucky, and Texas–ratified the amendment in 1920. The suffrage movement in Tennessee that had begun with Elizabeth Avery Meriwether’s lone crusade ended with a triumph that guaranteed millions of women the right to vote and changed the face of American politics forever.

Suggested Reading

Kathleen C. Berkley, “Elizabeth Avery Meriwether, An Advocate for her Sex: Feminism and Conservatism in the Post-Civil War South,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 34 (1984): 390-407; Anastatia Sims, “Powers That Pray and Powers That Prey: Tennessee and the Fight for Woman Suffrage,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 50 (1991): 203-25; A. Elizabeth Taylor, The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee (1957); Marjorie Spruill Wheeler, ed., Votes For Women! The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation (1995); Carol Lynn Yellin, “Countdown in Tennessee, 1920,” American Heritage 30 (1978): 12-23, 27-35