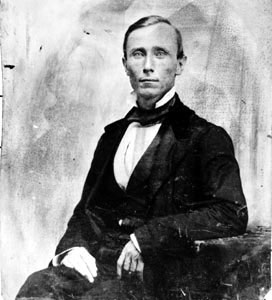

William Walker

William Walker was a leading filibuster in Latin America in the 1850s. He was born May 8, 1824, in Nashville and died in 1860 before a firing squad in Central America. His strange, brief career earned him the sobriquet “Grey-Eyed Man of Destiny.” He was controversial in the United States and feared in Central America. Trained as a physician in Pennsylvania and Paris (1843), he moved to New Orleans (1845), where he became a lawyer and idealistic newspaper editor. In 1850, after the death of his deaf-mute fiancée, Ellen Martin, Walker left for California, where he became involved in politics and emerged an advocate of Manifest Destiny.

In October 1853 Walker sailed with forty-five men for Mexico. Landing in Baja California, Walker declared the Republic of Lower California independent and named himself president. In January 1854 he declared the annexation of the adjacent state of Sonora and renamed the “country” the Republic of Sonora. Driven out of Mexico, Walker and his bedraggled forces returned to California and surrendered to U.S. troops. He stood trial for violation of U.S. neutrality laws and was acquitted. Although his expedition was a total failure, Walker was a hero to many Californians.

Walker next set his sights on Nicaragua, a fertile country with an important trans-isthmian commercial route but in chaos due to a long series of revolutions. To circumvent U.S. neutrality laws, Walker obtained a contract from President Castellón of the Democratic Party to bring as many as three hundred “colonists” to Nicaragua. The colonists received the right to bear arms in the service of the Democratic government against the rival Legitimist Party.

In June 1855 Walker and fifty-seven soldiers of fortune landed at the Nicaraguan Pacific port of Realejo. With Castellón’s consent Walker attacked the Legitimists in the town of Rivas, near the trans-isthmian route of the Accessory Transit Company, which Walker hoped to control. Walker’s men were defeated, but armed with six-shooters and superior rifles and motivated by a boisterous spirit of derring-do, they wreaked such havoc with the defenders of Rivas that the Americans established themselves as a feared force.

On October 13 Walker took the Legitimist capital, Granada, in a surprise attack. He then negotiated the surrender of the Legitimist army, the disbanding of the Democratic army, and the formation of a coalition government with himself as commander-in-chief of the Nicaraguan army. With the support of many Nicaraguans, Walker’s coalition government eventually received recognition by President Franklin Pierce’s administration in Washington. A bilingual newspaper, El Nicaragüense, was circulated in the United States, extolling Nicaragua for American colonization. Walker attracted recruits from among Americans crossing the isthmus en route to or from California.

Walker’s rapid rise to power disturbed many Nicaraguans and other Central American leaders who feared he intended to “Americanize” all Central America. In March 1856 a Costa Rican army invaded Nicaragua to remove Walker. Walker’s troops were defeated in fierce fighting in Rivas, but an outbreak of cholera forced the invading army to withdraw. By June, Walker’s coalition government was disintegrating, and the president and various cabinet members implored Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador to send armies to rescue the nation. Walker retaliated by declaring the president a traitor and calling for elections with himself as a candidate.

Walker was inaugurated as president of Nicaragua on July 12, 1856, and soon launched his Americanization program. English was declared an official language; currency and fiscal policy were reorganized to encourage immigration from the United States; and El Nicaragüense redoubled its recruitment efforts. Walker confiscated the estates of his Nicaraguan opponents and resold them to his American supporters. Finally, to secure support from the southern states of the United States, Walker annulled the constitutional prohibition against slavery.

Walker now faced a variety of enemies. On his inaugural day, Salvadoran troops entered Nicaragua and were later joined by Guatemalan and Honduran forces. The Pierce administration refused to recognize Walker’s new government. The British government encouraged Costa Rican opposition to Walker and provided arms for insurgents. Walker also made a powerful enemy in “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt. Walker’s lifeline to the United States was the fleet of river and lake steamers owned by the Accessory Transit Company, a lucrative Vanderbilt enterprise chartered by the Nicaraguan government. Walker unwisely agreed to transfer the charter to Vanderbilt’s business rivals. In retaliation, the “Commodore” sent agents to aid the Costa Ricans when they invaded Nicaragua again in November 1856.

Walker ordered Granada razed and concentrated his forces at Rivas. The Costa Rican capture of the Transit Company steamers left Walker with little hope of reinforcement. He held out for five months against superior forces until his own army was gradually reduced by starvation, disease, and desertion. On May 1, 1857, Walker surrendered to the U.S. naval officer who negotiated his capitulation.

Walker continued to believe himself the legitimate president of Nicaragua and mounted six return expeditions from the United States. Foiled by port authorities and bad luck, Walker was removed from Nicaragua a second time by the U.S. Navy. After an unsuccessful attempt to take the country via Honduras, he surrendered to a British navy captain, who turned him over to Honduran authorities. On September 12, 1860, Walker was executed for piracy in Trujillo, Honduras, where he is buried.

Suggested Reading

William O. Scroggs, Filibusters and Financiers: The Story of William Walker and His Associates (1916)