William Edmondson

Few folk artists can claim the widespread recognition by the world of fine art that William Edmondson achieved during his lifetime. The first African American artist to have a one-man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Edmondson continues to be recognized for the timeless power of his artistic vision of form reduced to its elemental geometry and his use of volumetric space.

Edmondson was born in Davidson County, the son of former slaves. He worked as a farm laborer and a racehorse swipe and then at the shops of the Nashville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis Railway until an accident forced him to retire in 1907. When he recovered, he worked at Woman’s Hospital (later Baptist Hospital), where he remained until the hospital closed in 1931. Throughout the Great Depression, Edmondson worked as a stonemason’s assistant, eventually developing his skills in carving.

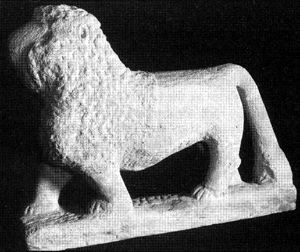

Funerary practices had long provided a traditional outlet for southern black culture, and Edmondson first emerged as an artist within this framework. A devoted member of the United Primitive Baptist Church, Edmondson often credited his artistic energy and purpose to divine vision. His earliest efforts were gravestones, sometimes composed of several stacked geometric elements, sometimes also incorporating bird or animal forms. From this traditional context, Edmondson’s carvings soon showed the influence of popular imagery in lambs, doves, and other forms. He expanded his repertory to include preachers, women, famous figures, and creatures of his imagination.

At the time Edmondson began to carve, there was a climate of growing appreciation for world folk and tribal arts. Edmondson’s self-described “stingy” carving expressed a minimalist philosophy toward his medium that was consonant with the strong movement toward abstraction and simplified form gaining currency among the Modernists. He carved directly into the limestone, barely freeing the image from its confines, and creating a sensual play of texture and shape between the contours of the form and the hard edges of the stone. Photographs of the sculptures convey an impression of monumentality. In truth, few were as large as twenty to twenty-five inches; the majority were on an intimate scale, limited by the odd shapes and small pieces of limestone available to him.

Awareness of Edmondson’s carvings reached the art world first through the efforts of his neighbor Sidney Hirsch, a member of the “Fugitive Poets,” who introduced the artist’s work to Alfred and Elizabeth Starr. The Starrs brought photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe to meet him. She documented his carvings and working environment, and introduced Edmondson’s art to Alfred H. Barr Jr., director of the Museum of Modern Art. In 1937 Edmondson’s sculptures were featured in a one-man show at the museum. The following year, his work was included in “Three Centuries of Art in the United States,” an exhibition organized by Barr for the Jeu de Paume in Paris. In 1939 and again in 1941 Edmondson was employed by the sculpture division of the Work Projects Administration. In 1973 he was the subject of Visions in Stone: The Sculpture of William Edmondson, written by Edmund L. Fuller and illustrated with over one hundred photographs of Edmondson and his carvings by Edward Weston and Roger Haile. Edmondson’s sculptures continue to be included in major art exhibitions, and his work is contained in many museum collections, including those of the Newark Museum in New Jersey, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., the University of Rochester Art Gallery in New York, the McClung Museum at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and the Tennessee State Museum in Nashville. A retrospective on his career was held at the Cheekwood Museum of Art in Nashville in 2000.

The concrete solidity of Edmondson’s carvings stand in ironic contrast to the fleeting record that remains of his life. His date of birth can only be guessed; a fire destroyed the family Bible and the record of his birth. His place of burial in Mount Ararat Cemetery in Nashville is unmarked, and the cemetery records were also destroyed by fire. Edmondson’s legacy survives, however, in the several hundred astounding carvings he created between 1931 and 1951.