University of Tennessee

The University of Tennessee was founded as Blount College, named for Territorial Governor William Blount and chartered on September 10, 1794, by the legislature of the Southwest Territory sitting in Knoxville. Located in a single building in a frontier village of forty houses and two hundred residents, the college appears to have been an overambitious undertaking. The motivations of the founders remain unknown, but they probably followed the postrevolutionary trend of college founding in order to create an educated citizenry for the new experiment in republican government. Although the first president was the local Presbyterian minister and seven of the first ten presidents were clergymen, the college was nonsectarian.

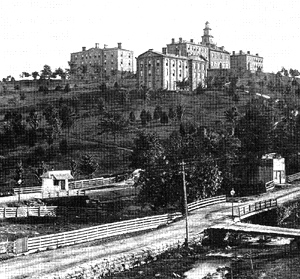

The college had a precarious existence. Only one student graduated, and the college depended on tuition for its financial support. In 1807 the state legislature rechartered the college as East Tennessee College and improved its financial prospects with a grant of public land. When the first president, Samuel Carrick, died in 1809, the college closed for a decade. East Tennessee College reopened in 1820, and, eight years later, moved to a new building on a hill outside town. By 1840 the institution had a new name, East Tennessee University, but its prospects continued to be uncertain. During the next twenty years, there were several presidents, and the faculty never numbered more than five. Approximately half of the 100 students were enrolled in the Preparatory Department, which acted as a secondary school to prepare students for admission to the regular collegiate course.

During the Civil War the university closed; both armies successively occupied the buildings as hospitals, and by the war’s end, the surrounding area was bare of any vegetation. Thomas Humes, who became president of the university in 1865, had been a Union sympathizer and used his influence to secure $18,500 from the federal government as restitution for wartime damages. In 1869 the state legislature designated the university as the recipient of the funds provided by the Morrill Act of 1862. This federal act awarded states land grants or scrip for the establishment of colleges and universities that would teach agriculture, the mechanical arts, and military science. This boon to the university’s fortunes made it the recipient of the annual interest on some $400,000, about $24,000.

In 1879 the state renamed the institution the University of Tennessee. In requesting the change, the trustees expressed the hope that the name change would inspire the legislature to provide regular financial support, but this generosity had to wait another twenty-five years. In the meantime, the institution sought to become a university in more than name by its own efforts. A somewhat hidebound and classically oriented faculty was reluctant to change the direction of the university, but the president who assumed charge in 1887 was not. Charles Dabney, the first president with an earned doctorate, reshaped the faculty and the institution. He successfully eliminated the preparatory department, ended the military regimen which governed student life, and began a law school and a department of education (under Philander Claxton). From 1902 until 1918, another innovation, the university’s Summer School of the South, enhanced the preparation of some 32,000 regional public school teachers. In 1892 women were admitted provisionally and granted unconditional admission the following year. A zealous advocate of improved public education for both whites and blacks and the author of the influential treatise Universal Education in the South (1936), Dabney proved too liberal for the trustees and left in 1904 for the presidency of the University of Cincinnati. His successor, Brown Ayres, continued to strengthen the university’s academic programs and persuaded the legislature to institute a series of regular annual appropriations for the institution’s operations, climaxed by the first million-dollar allocation in 1917.

In the twentieth century, the University of Tennessee emerged as a modern university, with professional schools of medicine, dentistry, nursing, and pharmacy, all located in Memphis. This institution is now known as the University of Tennessee, Memphis, the Health Services Center. The Knoxville campus offers programs in agriculture, architecture and planning, arts and sciences, business, communications, education, engineering, human ecology, information sciences, law, nursing, social work, and veterinary medicine leading to undergraduate, graduate, and professional degrees. Additional campuses are at Martin and Tullahoma, where a Space Institute was established in 1964. In 1969 the University of Chattanooga, a private institution founded in 1886, was added to the newly designated university “system,” with a Knoxville president and campus chancellors. From 1971 to 1979 the university maintained a campus in Nashville before it was ordered closed and merged with Tennessee State University as part of the state’s desegregation program.

Despite the financial support from public coffers, appropriations have never adequately funded the university. State funding currently provides about one-third of the institution’s budget. An aggressive development program instituted by President Andrew D. Holt (1959-70) produced gifts that resulted in an endowment of more than $410 million by the end of 1996.

Apart from the admission of women at the end of the nineteenth century, the most important change in the student body came in 1952 when African Americans were admitted to graduate and law schools under federal court order. Nine years later, the trustees voluntarily opened the doors to black undergraduates. Black enrollment currently varies from five percent on the Knoxville campus to 10 percent at Memphis and 13-14 percent at Chattanooga and Martin. In 2000 the university comprised a student body of more than 26,000 on the Knoxville campus and approximately four hundred undergraduate and graduate degree programs.

While the university has acquired a national reputation in both men’s and women’s athletics–the Lady Vols basketball team having won six national championships and the Volunteers football team winning the national championship in 1951 and 1998–the institution has also produced one Nobel laureate, seven Rhodes Scholars, six Pulitzer Prize winners, two National Book Award winners, nine U.S. senators, and one associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Its over 230,000 living alumni bear witness to the university’s success in fulfilling its mission of preparing Tennesseans for their roles as citizens of the state and nation and helping them realize their own potential.

Suggested Reading

Milton M. Klein, Volunteer Moments: Vignettes of the History of the University of Tennessee, 1794-1994 (1996); James R. Montgomery et al., To Foster Knowledge: A History of the University of Tennessee, 1794-1970 (1984)