Timber Industry

Although Tennessee’s earliest settlers appreciated the vast timber resources they discovered, the greatest timber extraction in the state’s history occurred between 1880 and 1920. Rapid deforestation by industrial loggers during this period caused long-term environmental changes and notable revision of state and federal policies.

Early European settlers extolled the wonders of the rot-resistant American chestnut trees, which made up as much as 25 percent of the forest. They proceeded to build durable homes and fences from them and to clear the woods for agriculture. By the early nineteenth century, a rudimentary iron industry also found hardwood (deciduous trees) valuable to fire small blast furnaces. A typical, eight-foot-square forge required a layer of charcoal four feet thick to melt four hundred pounds of ore in two hours. Not surprisingly, the woods around the forges were typically cut down, and slag from such operations can still be found. Demand for wood to produce charcoal encouraged an 1809 state law that permitted ironmakers to acquire large tracts of land just for harvesting wood. In the 1830s, for example, the Tellico Plains Iron Works began harvesting trees on the Tellico River for the manufacture of pig iron and, eventually, cannon balls and ammunition for Confederate troops.

Large-scale timber and mining would not be profitable, however, until the railroad moved to Tennessee. Despite repeated petitions, by the 1850s the state only had twelve hundred miles of track. This relatively slow entrance into the new transportation age probably protected Tennessee forests longer than the neighboring states of Kentucky and Virginia. Soldiers passing through the state during the Civil War frequently commented on the verdant natural resources, particularly in the eastern part of the state; some of these men later became investors and entrepreneurs in the turn-of-the-century timber boom. As railroads began carving up the state after the war, struggling farmers picked up seasonal income by cutting and selling medium-sized species such as locust to the companies for railroad ties. Others sold bark from their woodlots to the nascent tanning industry.

Beginning in the 1870s, Nashville and Memphis promoters welcomed Northeast lumbermen into the state. In 1881 Southern Lumberman, which remains the major trade association publication for southern hardwood companies, began publication in Nashville. Nashville companies got much of their hardwood from small entrepreneurs along the Cumberland River. Enterprising men cut trees during the winter and when spring rains swelled the streams that fed the Cumberland, they floated out rafts of logs and sold them to the Nashville mills. The principal species were oak and poplar, but a few mills such as Prewitt-Spurr specialized in cedar buckets and churns. In 1910, thirty-two hardwood mills operated in Memphis. Furniture makers from all over the nation bought wood in Memphis, which billed itself as the Hardwood Capital of the World.

In East Tennessee, outside capitalists such as Glasgow’s Scottish Carolina Timber and Land Company also sought specialty wood, especially cherry and walnut. The company built a mill and log boom at Newport during the 1890s but could not keep the operation solvent for long because of transportation problems. At the same time, a Michigan investor, W. E. Heyser, built a mill in Chattanooga and towed logs down the Little Tennessee to his operations. Because of the inaccessibility of the mountains, though, federal foresters Horace B. Ayres and William W. Ashe reported that the forests in the eastern part of the state remained largely intact in 1901.

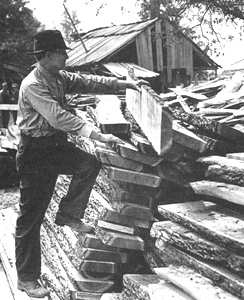

The invention of steam-powered skidders and band sawmills soon improved profitability in remote locations. In Monroe County, a group of Pennsylvania businessmen operated the Tellico River Lumber Company. New York businessmen operated the Tennessee Timber Coal and Iron Company in Cumberland County. Two Cincinnati investment groups ran the Grand View Coal and Timber Company near Chattanooga and the Conasauga Lumber Company in Polk County. Wilson B. Townsend, a Pennsylvania lumberman, became interested in the Little River area after the Schlosser Leather Company financed a railroad into nearby Walland. Townsend already controlled major logging operations in Pennsylvania and coal, clay, tile, and railroad holdings in East Kentucky when he moved into Tuckaleechee Cove in 1901. He built a railroad, mill, and company town, which residents named Townsend in his honor. As a well-financed businessman, he could afford the latest technology and so switched his operations from circular saws to band saws, which allowed cutting very thick logs with less waste. Townsend invested in steam-powered skidders that could transport oak and chestnut trees as small as ten inches as far as five thousand feet. By 1910 his Townsend operations were producing 120,000 board feet per day.

Timber barons also relied on cheap, nonunion labor in Tennessee. Poor farmers moved to the temporary lumber camps and lived with their families in boxcars or “setoff” houses eight by ten feet wide that could be moved from site to site. In 1912 Tennessee lumber workers put in a sixty-hour week for fourteen cents an hour. Wages did not rise even when demand for southern hardwoods increased. When war broke out in Europe in 1914, the demands on southern forests, especially walnut for gun stocks accelerated, and did not abate with the return of peace. White County timber was especially targeted for gun stock production.

Turn-of-the-century lumbermen took so many trees so quickly that Gifford Pinchot, head of the U.S. Forest Service, predicted that all the timber in the United States would be gone in twenty years. Such dire warnings helped lead the industry toward the establishment of National Forests; indeed, many lumbermen, including Townsend, were convinced that the Forest Service would save them money in taxes and management. The depletion of forest lands resulted in a dramatic loss of wildlife as habitat was destroyed. To protect game and improve tourism, Tennessee initiated its first game laws and under Governor Austin Peay established a Department of Forestry. Careless management by timber companies allowed fire to spread in the clear-cut mountainsides, and erosion further damaged the land. This rapid deforestation and soil loss created high and low runoff patterns, and major flooding followed. Partially in response to swollen riverways and denuded land, the federal government in the 1930s initiated such major reforms as the Tennessee Valley Authority and the projects of the Civilian Conservation Corps as well as the designation of the Cherokee National Forest and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Suggested Reading

James L. Bailey, comp., Tennessee Timber Trees (1962)