Ruskin Cooperative Association

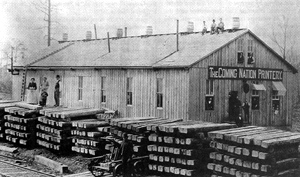

The Ruskin Cooperative Association (RCA) existed in Dickson County from 1894 until 1899. Established at Tennessee City, the colony soon moved five miles away to a site by a large cave on Yellow Creek which still bears the name Ruskin. Named for English social critic John Ruskin and inspired also by Americans Edward Bellamy and Laurence Gronlund, this secular cooperative colony grew from the efforts of Julius Wayland and profits and publicity from his socialist weekly, The Coming Nation. Wayland relocated the paper from Versailles, Indiana, and it became a vital part of the RCA. Colonists came primarily from the middle and far West. While membership, obtained by purchasing a five-hundred-dollar no-yield share and demonstrating a commitment to cooperative living, never exceeded a few hundred, the eyes of the world were upon the experimental colony.

The experiment did not lead to anything larger, however. The charismatic and entrepreneurial Wayland left after leading Ruskin for only a year, exacerbating factionalism within RCA. While some Ruskinites sought to apply radical ideas and help bring about a “coming nation” based on cooperation over competition and common over individual ownership, others sought and found at Ruskin a haven for threatened American values such as economic and political independence. Tensions between these forward- and backward-looking visions, which Wayland may have been able to reconcile, ultimately destroyed the RCA.

Yet in its short existence, the colony developed many notable practices within the cooperative commonwealth. These included the use of scrip money, several entrepreneurial ventures, and the implementation of innovative educational practices. By fashioning a system based upon the labor theory of value to counteract the “wage slavery” of the industrial age, the RCA sought to reward laborer as producer. Colonists worked for scrip money–currency based upon work hours–which could be exchanged either for labor or for goods priced upon the same principle. Labor included newspaper work, farming, and preparing meals for the cooperative dining hall. Members also operated and produced goods for several mail order ventures undertaken to keep RCA afloat, including the production and sale of suspenders, natural chewing gum, and cereal coffee. As the latter two products imply, the colony was within the same cultural milieu as sanitaria of the day, including those of John Harvey Kellogg and C. W. Post. Colonists grew their own food, many practiced vegetarianism, and alcohol was forbidden on colony grounds.

RCA also offered self-improvement through free medical care and free education for members. From its beginnings and by March 1896, under the leadership of Isaac Broome, the colony sought to implement innovative educational ideas. In the spirit of John Ruskin, Julius Wayland and his successors saw better education as fundamental to the transformation of society, an essential if “ignorance is to be dethroned.” And the coming nation would need a class of “philosopher kings” to lead it. Most colony leaders stressed childhood education, including the new concept of kindergarten, as well as higher and continuing education for adults. They fostered the latter with an extensive library and frequent lectures and performing arts events at Ruskin. Broome’s crowning achievement was to have been the Ruskin College of the New Economy, which would reflect John Ruskin’s own emphasis on experiential learning and the importance of fostering an aesthetic appreciation for life’s endeavors.

However, the growing majority at Ruskin had little appreciation for the ideologues’ efforts on their behalf. The college never developed beyond a grand vision and a groundbreaking ceremony featuring Henry Demarest Lloyd. Many Ruskinites, an embittered Broome later reflected, preferred to “smoke, gossip, and spit tobacco” rather than develop their minds. The seemingly harmless split between those who sought escape from a changing world and the more doctrinaire who sought to revolutionize society through the microcosm of the RCA ultimately destroyed the colony.

By July 1899 factionalism had brought disintegration. The cooperative was placed in receivership, ending two years of lawsuits between the two factions over issues relating to ownership and control of the RCA. By this point, many from both sides had given up the cause, and efforts by several dozen of the less doctrinaire faction to continue the cooperative and the newspaper on swampy land in Duke, Georgia, were short-lived.

Suggested Reading

Clay Bailey, “Looking Backward at the Ruskin Cooperative Association,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 53 (1994): 100-113