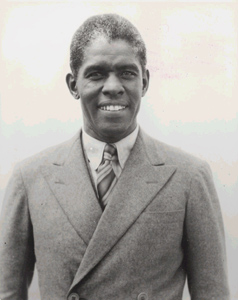

Roland Wiltse Hayes

Roland Hayes was one of the most popular opera singers of his generation and an important supporter and mentor to such significant African American artists as Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson. Born in Curryville in northern Georgia to former slaves William and Fanny Hayes in 1887, Hayes lived a sharecropper’s life as a boy. His father died when Hayes was eleven and soon thereafter he and his brothers moved to Chattanooga. In addition to working at local industries, Hayes became part of a youth quartet that sang for pocket change from travelers at the train station.

His turn toward classical training began in Chattanooga at the age of fifteen, when he met the pianist Arthur Calhoun, who encouraged his singing and introduced Hayes to recorded performances of famous opera singers. Hayes soon learned several basic arias and lieder by listening to the records and following the performers. Calhoun, who had studied at the Oberlin Conservatory, recognized that Hayes had been blessed with remarkable talents. He convinced Hayes to leave Chattanooga and pursue professional music training. Calhoun wanted Hayes to attend Oberlin, but Hayes only made it as far north as Nashville, where he enrolled at Fisk University. Fisk officials realized that Hayes had little education and placed him in the preparatory school, even though he was already twenty years old.

Hayes and Fisk did not mix well, and he was kicked out of the school. Hayes believed his dismissal resulted from his persistent singing for various clubs and organizations without prior approval of the music department. He moved to Louisville where he worked as waiter and sang at a local theater and in various churches. In 1911 the Fisk Jubilee Singers–then a quartet not under the administration of the school’s music department–asked Hayes to join them for performances in Boston. When the Jubilee Singers left, Hayes stayed in Boston, where he continued his education with Arthur J. Hubbard. Music scholars date Hayes’s professional career to 1916 when he appeared in various concerts. The following year Hayes rented Symphony Hall in Boston in order to present his own recital. This daring maneuver paid off both artistically and financially. Critics met his performance warmly, and from that point on Hayes performed steadily across the western world.

In 1920 he moved to London to perform and continued his training with lieder expert George Henschel over the next several years. Highlights of this period include a command performance for the king and queen at Buckingham Palace in 1921 and concert performances in London, Paris, Berlin, and Vienna.

Hayes’s reputation as lyric tenor who presented accessible but varied programs of lieder proved very popular in the United States. From the early 1920s to the 1940s he toured constantly, singing to nonsegregated audiences. For instance, he sang to nonsegregated audiences several times at the famed Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C., long before that same venue denied Marian Anderson a chance to perform at the hall in 1939. Artistry and world fame, however, still meant little to many in his native South. When his wife Helen Mann Hayes and daughter Afrika Fanzada Hayes were arrested for sitting in a white-only area in Rome, Georgia, in 1942, Hayes attempted to intervene, for which he too was arrested, beaten, and placed in jail.

Hayes promoted young African American musicians and traditional African American music. He compiled a collection of African American spirituals, My Songs: Aframerican Religious Folk Songs (1948). He became a music professor at Boston University in 1950. The NAACP gave Hayes its Spingarn Medal in 1924. In the 1960s and 1970s he received numerous awards and accolades including a tribute concert at Carnegie Hall in New York City for his pioneering work in classical music.

Suggested Reading

Mackinley Helm, Angel Mo and Her Son (1942); Langston Hughes, Famous Negro Music Makers (1955)