Railroads

Tennesseans considered railroads as early as 1827, when a rail connection between the Hiwassee and Coosa Rivers was proposed. The general assembly granted six charters in 1831 for railroad construction, but these early efforts failed when financial support did not materialize. Early railroad fever struck hardest in East Tennessee. Beginning in 1828 Dr. J. G. M. Ramsey of Knoxville advocated a rail connection between South Carolina and Tennessee. In 1831-32 the Rogersville Rail-Road Advocate (possibly the first railroad newspaper in the United States) favored an Atlantic connection through Virginia.

West Tennesseans also envisioned connections to the Atlantic coast. The Memphis Railroad Company (chartered in 1831, renamed Atlantic and Mississippi in 1833), hoped to connect Memphis with Charleston. Another scheme attempted to link Memphis with Baltimore.

Tennessee’s legislature enacted an 1836 law requiring the state to subscribe to one-third of railroad and turnpike company stock (the subscription was raised to one-half in 1838). When the state-stock system stumbled after the Panic of 1837, the ironic outcome was completion of Middle Tennessee turnpikes rather than railroads. The state aid laws were repealed in 1840 under Governor James K. Polk.

Although in force only a few years, the state internal improvement laws spurred some railroad developers to action. The Hiwassee Railroad did not qualify for the state subscription but began construction in 1837 near Athens. Despite achieving Tennessee’s first actual railroad construction, the Hiwassee failed in 1842. The LaGrange and Memphis Railroad was the only railroad to qualify for state subscription, and in 1842 it became the first railroad to actually operate a train in Tennessee. A few months later the county sheriff took possession due to unpaid court judgments.

Tennessee’s railroad interest revived in the late 1840s, encouraged by successful neighboring states. Georgia’s Western and Atlantic was already headed toward the Tennessee River, and it reached Chattanooga by l850, a development that renewed the hopes of Knoxville and Memphis and created the first serious railroad interest in Nashville.

In 1848 the general assembly endorsed bonds of the Nashville and Chattanooga (N&C), but the East Tennessee and Georgia (ET&G) won a precedent-setting direct loan two years later. The General Internal Improvement Law of 1852 provided state loans to railroads at $8,000 per mile ($10,000 per mile by 1854). Every Tennessee antebellum railroad (except the N&C) received grants under this system.

The N&C was the first railroad completed in Tennessee. Incorporated in 1845, it reached Chattanooga by 1854. It was the only state-aided railroad to avoid financial loss to the state. Associated branch lines were completed in the 1850s: the McMinnville and Manchester; the Winchester and Alabama; and the coal mine branch to the Sewanee Mining Company at Tracy City. Another associated line, the Nashville and Northwestern (N&NW), was intended to connect Nashville to the Mississippi River at Hickman, Kentucky. Construction began at Hickman, but the line had been extended eastward only to McKenzie by the Civil War; the eastern end ran only a few miles from Nashville, where it was captured by the Union army, who continued it to Johnsonville on the Tennessee River (the remaining gap was completed after the war).

The Memphis and Charleston (M&C), incorporated in 1846, ran across Mississippi and Alabama to reach Stevenson, Alabama by 1857, where it connected with the N&C, thus linking Memphis to the Atlantic via the N&C and the Western and Atlantic.

The ET&G, chartered in 1848, revived the Hiwassee Railroad. Running from Dalton via Athens and Loudon to Knoxville by 1855, it was the second railroad completed in Tennessee. A more direct route between Cleveland and Chattanooga was completed in 1858. The East Tennessee and Virginia (ET&V), chartered in 1849, was completed from Knoxville to Bristol in 1858, ending East Tennessee’s railroad isolation.

Nashville gained rail access to the North through Kentucky. Louisville city subscriptions and Tennessee state aid financed the Louisville and Nashville (L&N), incorporated in Kentucky in 1850. Competitive subscriptions among local governments determined its Tennessee route. Completed in 1859, it hosted an excursion intended to preserve the Union. Several other Middle Tennessee railroads provided Nashville connections. The Nashville and Decatur (N&D) ran from Nashville through Columbia to Tennessee’s southern border, where it connected with the M&C and an Alabama railroad to Decatur (it also extended from Columbia to Mt. Pleasant). The Edgefield and Kentucky (E&K), completed in 1860, ran from the Nashville suburb of Edgefield to Guthrie on the Kentucky boundary.

Memphis also established railroad access to Louisville: the Memphis and Ohio (M&O) ran from Memphis to Paris; the Memphis, Clarksville, and Louisville ran from Paris to Guthrie; and the L&N constructed a branch from Bowling Green to Guthrie.

West Tennesseans gained rail access to Mobile, New Orleans, and Columbus, Kentucky, due to the rivalry between New Orleans and Mobile to establish rail connections to the mouth of the Ohio River. The Mobile and Ohio (M&O) reached from Columbus to Jackson, Tennessee, in 1858, and to Mobile in 1861. The Mississippi Central and Tennessee connected with the M&O in 1860, giving New Orleans access to the Ohio a year before its rival Mobile. The Mississippi and Tennessee completed a line from Memphis to Grenada, Mississippi, in 1861, giving Memphis access to New Orleans via the Mississippi Central.

Tennesseans took preliminary steps to begin a transcontinental route through Memphis, Little Rock, and El Paso, but the Civil War dashed any hopes that the South would participate in a railroad to the Pacific.

Tennessee railroad equipment of the 1850s was primitive. Railroad track (mostly unballasted) consisted of light T-section wrought-iron rail on untreated crossties. Tennessee track adopted the usual Southern broad gauge of five feet. The typical steam locomotive was the American type, characterized in the Whyte system as the 4-4-0 (four leading wheels, four drive wheels, no trailing wheels). Colorfully painted and picturesquely named, they were wood fueled, requiring a distinctive balloon smoke stack. Rolling stock utilized wooden construction, link-and-pin couplers, cast iron wheels, and hand brakes. Freight cars were limited to boxcars, flatcars, and gondolas. Passenger cars were crude open air coaches equipped with wood stoves, kerosene lamps, and hand-pumped water. Antebellum railroad depots in larger cities were substantial brick buildings, but elsewhere they were simple wooden structures, often lacking protective canopies for passengers or freight loading ramps.

By 1860 Tennessee had completed 1,197 miles of track, which represented about 13 percent of the South’s total of 9,167 miles. Southern railroads represented only about 30 percent of the total national rail mileage, and they were comparatively small organizations with inferior equipment running on lighter rail. However, Tennessee’s strategic location as a border state between North and South destined its railroads to play a significant role in the Civil War.

In the spring of 1862, with the fall of Forts Donelson and Henry to Federal gunboats, Confederate General Albert S. Johnston realized that Nashville was indefensible and retreated toward Murfreesboro. Plans to evacuate supplies from Nashville faltered when panicked citizens and bridge washouts overwhelmed southbound railroads. Johnston, aware that he could not defend both Middle Tennessee and the Mississippi, decided to protect the river and Memphis. The most strategic point was the railroad junction at Corinth, Mississippi, where the M&O joined the M&C. Using railroads extensively, Johnston concentrated troops from all over the Confederacy at Corinth. Meanwhile, Federal General Ulysses S. Grant gathered his forces at nearby Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River. The two forces met in a major battle near Shiloh Church in April 1862. Johnston was killed, and the Confederates retreated, leaving Union forces in control of the only Confederate rail line between Virginia and the Mississippi River. The outcome disabled Confederate rail transport west of Chattanooga and north of Vicksburg and permitted Union rail access southward to Alabama and Mississippi and eastward to Stevenson, Alabama, near the important rail junction of Chattanooga.

Grant was assigned to guard the railroads providing communication with the Mississippi, and General Don Carlos Buell was assigned to take Chattanooga. But Confederate General Braxton Bragg delayed federal movement toward Chattanooga with a series of harassing raids by Nathan B. Forrest and John H. Morgan against the federally occupied M&C and N&C railroads, allowing time for Confederate troops to move by rail from Tupelo to Chattanooga. Grant created a defensive railroad triangle encompassing Memphis, Humboldt, and Corinth.

The state’s railroad system became of even more strategic value in 1863. After the battle of Stones River, massive quantities of supplies arrived at Murfreesboro via the N&C, and Federal forces erected the enormous Fortress Rosecrans to protect this critical supply depot.

The Confederates decided to concentrate additional forces at the center where Bragg and Rosecrans were evenly matched. In a remarkable transportation feat, Confederate troops traveled by rail from Virginia (1,000 miles by a difficult indirect route, necessary because Federals had taken Knoxville), while others marched from Mississippi. In September 1863 Rosecrans advanced to Chattanooga, and Bragg withdrew to Georgia. Rosecrans recklessly pursued Bragg until the Confederates delivered a severe blow at Chickamauga, forcing the damaged Federal army to retreat back to Chattanooga. Bragg advanced on Chattanooga, occupying Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, from which vantage point his forces could control the city’s transportation. With Federal forces reduced to near starvation, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton devised an ambitious plan for the massive railroad transport of Federal troops from Virginia to relieve the siege of Chattanooga. Generals George H. Thomas (who had replaced Rosecrans) and Grant used these forces to conquer Chattanooga, effectively delivering all of Tennessee to Federal control. This amazing transportation feat proved that, under the control of strong centralized authority, railroads could project substantial military force across great distances within a short time.

In 1864 Confederate General John B. Hood conducted raids against the Federal rail lines to Chattanooga. Hood invaded Tennessee, hoping that the Federals would follow him to supposedly advantageous terrain. Sherman sent Generals Thomas and John Schofield to Tennessee, where they defeated the Confederates at the battles of Franklin and Nashville in late 1864. The Confederates retreated from Tennessee for the last time, leaving the state’s railroads completely in Federal hands. Although the Confederate railroads had served their military forces well, when Federal forces secured control of the Southern railroad network, they solidified access to the superior manufacturing capabilities of the North, which ultimately led to Union victory.

The Civil War left Tennessee’s railroads damaged and most of its railroad companies in financial straits. Governor William G. Brownlow attempted to reconstruct the whole railroad system, and by 1869 the general assembly had appropriated $14 million dollars for railroad companies. However, widespread corruption among legislators and railroad officials led to fraudulent use of the funds. Tennessee defaulted on bonds maturing in 1867-68, causing a severe drop in the state’s securities and excessive speculation in its bonds. Investigative committees had little effect, and suggestions of repudiating bonds were silenced by threats of military reconstruction by Washington Radicals. Brownlow was succeeded by DeWitt C. Senter, who eventually abandoned Radicalism and worked with the Conservative legislature to reverse Radical measures. In 1879 the general assembly and Governor Albert S. Marks uncovered the flagrant corruption of railroad and government officials.

Especially during the 1880s, Tennessee railroads expanded substantially. The railroad network nearly tripled its antebellum size to a substantial 3,131 miles by 1900. Simultaneously, railroad track and equipment evolved into more sophisticated forms for more effective passenger and freight transportation. However, the biggest change in the state’s railroads was in the gradual shift of finance and control from local parties to northern interests. By the 1890s, the bulk of Tennessee’s railroads were consolidated into just three major systems dominated by northern control: the Southern, the L&N, and the Illinois Central (IC). Amazingly, these three large systems would continue to maintain their corporate identities for nearly a century!

The Southern Railway Security Company, controlled by the Pennsylvania Railroad, pioneered use of a holding company to consolidate Southern railroads: it controlled the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia (ETV&G–formed by the 1869 merger of the ET&G and ET&V) by 1871 and leased the M&C in 1872. The Pennsylvania abandoned its southern initiative after the Panic of 1873. The rapidly growing ETV&G had absorbed the M&C by 1884, and was in turn acquired by the Richmond and Danville in 1887. These companies entered receivership in 1892, and J.P. Morgan reorganized them by 1894 to form the long-lived Southern Railway. The Southern acquired the Cincinnati Southern (Cincinnati to Chattanooga) in 1895.

The L&N remained prosperous while expanding rapidly in the late nineteenth century. This dominant Middle Tennessee line absorbed the Memphis, Clarksville, and Louisville by 1871; the M&O and the N&D by 1872; the E&K in 1879; and the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis (previously formed when the N&C acquired the N&NW in 1872) in 1880. Although the railroad remained in local and southern hands into the 1880s, the Atlantic Coast Line actually controlled the L&N by 1900.

The IC absorbed several West Tennessee lines after the war, beginning with the New Orleans, St. Louis and Chicago in 1877 (a consolidation of the New Orleans, Jackson, and Great Northern and the Mississippi Central with its 1873 extension from Jackson, Tennessee, to Cairo, Illinois). The IC acquired the Mississippi and Tennessee by 1889, and the Chesapeake, Ohio and Southwestern (C. P. Huntington’s Louisville to Memphis line) in 1893, giving control of most West Tennessee railroads to Edward H. Harriman. (Tennessean Casey Jones achieved his folksong fame on the IC during a fatal run south from Memphis on April 30, 1900.)

Tennessee’s railroad technology developed rapidly during the late nineteenth century. A massive 1886 effort converted the antebellum Southern broad gauge track (five feet between rails) to the national standard gauge (four feet, eight and one half inches), eliminating many costly transfers at junction points. Track was ballasted and made more robust, and steel rail was introduced in the 1870s. Railroads began to use creosote on wooden bridges and trestles (crossties remained untreated), and metal components appeared on large bridges. Locomotives grew larger and used more efficient coal fuel. Specialized freight locomotives such as the Mogul (2-6-0) in the 1870s and the Consolidation (2-8-0) in the 1880s appeared, and by the 1890s, Ten Wheeler (4-6-0) passenger engines had begun to ply the tracks. Wooden construction still dominated rolling stock, but refinements included air brakes (1870s), steel-tired wheels (about 1880), and automatic couplers (required by the Federal Safety Appliance Act of 1893). By the 1880s passenger cars acquired gas lighting, enclosed vestibules, and steam heating. By the 1890s passenger cars had wide vestibules, air-pressured water supplies, and electric lights powered by axle generators and batteries. The Railway Post Office car appeared in 1869, and sleeping cars (invented in the North in 1864, but slowly adopted in the South) became more common. Freight cars increased in capacity, some utilizing steel underframes as early as the 1870s. Ice-bunker reefers (for refrigerated fresh produce) appeared in the 1870s.

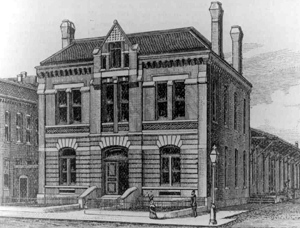

Depots acquired formal stylistic traits, although there was a divergence between urban and rural stations. Elaborate urban depots reflected Victorian Gothic, Richardsonian Romanesque, Neo-Classical, and Beaux Arts Classical styles. Many rural depots displayed Carpenter Gothic features, while others exhibited Stick, Eastlake, and Queen Anne characteristics. Some railroads adopted standardized designs and color schemes for their buildings.

Tennessee’s late nineteenth-century railroad growth reflected a larger economic revitalization, based on extractive industries controlled by northern interests. Numerous small railroads developed specifically for timber/lumber, iron mining/smelting, coal, and phosphate transportation. The mountainous topography of East Tennessee led to the creation of unusual lines which were uniquely configured to accommodate sharp curves and steep grades. These railroads adopted narrow gauge (three feet) track and geared locomotives to access valuable but remote resources.

The first two decades of the twentieth century involved moderate growth for Tennessee railroads, culminating in the all-time maximum state rail mileage of 4,078 miles in 1920. The Southern, L&N, and IC continued incremental growth; L&N notably gained a foothold in East Tennessee in 1905, with completion of its Atlanta to Cincinnati line which passed through Knoxville.

Creosote treatment (previously confined to bridges and trestles) finally was extended to crossties around 1912. More powerful locomotives evolved, including the Mikado (2-8-2) for freight and the Pacific (4-6-2) for passenger use. Passenger cars obtained steel underframes, and by 1913-14 all-steel coaches and diners appeared. Freight cars grew in size and developed steel-framed superstructures. Sophisticated signaling and control systems evolved, contributing to both efficiency and safety. Tennessee’s most impressive depots, designed to serve multiple railroads, appeared during the early twentieth century; especially notable are Nashville Union Station (1900) and Memphis Union Station (1913).

The major effect of World War I was the imposition of federal control on Tennessee’s railroads. A centralized system which consolidated operational activities and facilities during the war replaced rivalry between competitors. Financial difficulties beset the railroads when federal control was lifted in 1920–even the relatively prosperous L&N experienced a deficit, its first since 1875.

After 1920 Tennessee railroads began a long decline. The primary cause was the development of an extensive highway network with its growing fleet of cars, buses, and trucks. Airlines contributed to the decline in rail passenger operations. New pipeline systems and improved water transport affected rail freight operations. Excessive government regulation, along with preferential funding of newer transportation modes, also contributed to overall railroad decline. Tennessee’s total railroad mileage continued to diminish–to 3,573 miles by 1940–as did the railroads’ share of transportation traffic.

During the 1920s and 1930s (and despite the damaging effects of the Great Depression), the railroads attempted to fight back by developing more efficient freight equipment, additional passenger comforts (especially air conditioning), and faster speeds (as suggested by the adoption of streamline design). These measures only marginally slowed the railroads’ loss of freight and passenger traffic, however.

The increased rail traffic during World War II improved railroad profitability. Operating on considerably less total track mileage than in World War I, technological improvements allowed railroads to carry larger volumes of traffic during World War II. In contrast to the excessive government intrusion of the earlier war, during the second conflict the railroads remained under private control.

Diesel locomotives first appeared on Tennessee railroads during the early 1940s. Diesels were more efficient and required less maintenance than steam engines, allowing railroads to replace elaborate steam locomotive servicing facilities with simpler diesel facilities. Most Tennessee railroads were completely dependent upon diesel power by the mid-1950s.

The postwar years brought further decline in Tennessee railroads. Railroad traffic share continued to diminish, substantially in freight transportation and to virtual extinction in passenger operations. By 1995 continued abandonment had reduced Tennessee’s total rail mileage to only 2,634 miles–smaller than the state’s 1890 rail network.

In the late twentieth century corporate consolidation again emerged as a major theme in the state’s railroad history. The Southern Railway became part of Norfolk Southern as a result of the 1982 consolidation of the Southern with the Norfolk and Western. The L&N became one of the Family Lines created by the Seaboard Coast Line (SCL) in 1972. Most of the Family Lines were formally merged in 1983 to form the Seaboard System Railroad, which was renamed CSX Transportation in 1986. CSX inherited the traditional Middle Tennessee dominance exercised by the L&N for nearly a century and broadened its influence in East Tennessee through another merged Family Line, the Clinchfield Railway. Widely known for its remarkable engineering through challenging mountainous terrain, the Clinchfield crossed Tennessee (a major shop facility is located at Erwin) on its passage from South Carolina to Kentucky. The Illinois Central merged with the Gulf, Mobile and Ohio in 1972 to form the Illinois Central Gulf Railroad, owned by IC Industries. It serves primarily the western division of Tennessee, with strong connections to the Gulf coast and to northern cities.

The Tennessee Central Railroad, created by controversial promoter Jere Baxter in the 1890s, fought L&N’s Middle Tennessee monopoly for many years, managing to survive until bankruptcy in 1968, after which its remaining assets were divided up in 1969 between the Southern and L&N.

Tennessee railroads continue to evolve technologically to cope with changing economic conditions. The once vast fleet of boxcars has been mostly replaced by “piggybacking” of trailer-on-flat-car (TOFC) and container-on-flat-car (COFC). TOFC/COFC is a key component of the intermodal freight concept which seeks to minimize en route handling between various modes of transportation. Another method for lowering costs involves unit trains: long strings of high-capacity rolling stock which convey massive quantities of bulk commodities. Unit trains carry coal, Tennessee’s top bulk commodity.

The Staggers Act of 1980 reduced the federal regulation of railroads, allowing rail companies to respond more effectively to market conditions in state, national, and even international settings. Tennessee’s bulk freight rail traffic reflects a relatively healthy economic situation, with the state ranking ninth in total tons carried by rail. Although passenger rail traffic has virtually disappeared in Tennessee, with Amtrak operating stations in only Newbern and Memphis, severe highway congestion around major urban centers has led to interest in the establishment of commuter rail links to surrounding suburban areas.

Suggested Reading

Stanley J. Folmsbee et al., Tennessee: A Short History (1972); Kincaid A. Herr, Louisville and Nashville Railroad, 1850-1963 (1964); John F. Stover, The Railroads of the South, 1865-1900: A Study in Finance and Control (1955); Elmer G. Sulzer, Ghost Railroads of Tennessee (1975); George Edgar Turner, Victory Rode the Rails: The Strategic Place of the Railroads in the Civil War (1953)