Medicine

A rich source of herbal and root remedies derived from indigenous American plants greeted newcomers to the Tennessee backcountry in the eighteenth century. James Adair, an early white Indian trader of the trans-Allegheny region that is now Tennessee, described remedies skillfully applied by the Cherokees to heal the sick, injured, or infirm. Indians, Adair observed, always carried with them snakeroot, or wild horehound, plantain, and other herbs to curb the life-threatening effects of snake bites. Unfortunately for the Cherokees, the bounteous medicinal offerings of the Great Smoky Mountains shrank before the decimation stemming from the smallpox white settlers brought with them to America.

While traders in the west encountered Native American healers, colonists in the east tenaciously clung to remedies originating in plants imported from their native lands or those transplanted to the New World. Only gradually did indigenous remedies meld with the knowledge colonists brought with them on their trans-Atlantic crossings. The extent of the influence of Native American healing practices upon white practices is unknown and likely involved a process of adding to known remedies rather than supplanting them.

If the impact of traditional Indian medicinal remedies is difficult to assess, then remedies brought to America by African Americans present an even greater challenge. Self-care and medicine as practiced by African American doctors during the colonial era is little understood. Certainly, the African tradition of relying on conjurers traveled to America. Whites had little trust in blacks’ medical remedies; thus whites’ and blacks’ treatments often competed. Only rarely did whites adopt blacks’ remedies as legitimate healing practices.

Sullivan County records the first white physician in Tennessee. Dr. Patrick Vance immigrated to America in 1754 and moved to Tennessee following the American Revolution. Dr. Elkannah R. Dulaney joined Vance in 1799 or 1800. Dulaney typified the active interest many physicians took in their communities. Remuneration was meager and physicians like Dulaney, who served six terms in the state legislature, became involved in civic affairs. By the time Dulaney’s son, William R. Dulaney, was born in 1800, it was customary for aspiring physicians to apprentice themselves to a physician in their community, then to attend a medical training program, usually a four-month course of lectures spread over two years, with the second course a repeat of the first. William Dulaney completed his studies in 1839 at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, a school that supplied many of Tennessee’s early physicians.

Reverend Samuel Carrick, noted for his pastoral and educational accomplishments, dispensed medicines before Dr. James Cozby, Knoxville’s first physician, settled in the area. In 1794 two other physicians, Dr. Thomas McCombs and Dr. Robert Johnson, joined Cozby. Dr. Joseph Churchill Strong opened his practice in 1804 and served as preceptor to a number of ambitious physicians. Dr. J. G. M. Ramsey studied with Strong for two years, then matriculated at the University of Pennsylvania, one of America’s oldest medical schools.

As white settlers migrated westward to the Cumberland settlement at what is now Nashville, physicians followed. The first physician of record was Dr. James White. An exceptionally well-trained graduate of the University of Edinburgh, White was succeeded by Dr. John Sappington and his brother, Dr. Mark B. Sappington, who arrived in Nashville in 1785. In 1806 University of Pennsylvania-trained Dr. Felix Robertson opened a medical practice in Nashville. The first white male child born at the settlement, Robertson was a son of Nashville founder, James Robertson, and Charlotte Reeves Robertson. Felix Robertson grew to become a leading figure in Nashville’s civic and medical circles. Besides being mayor of the city, he served as president of the Medical Society of Tennessee (1834-40) and is credited with organizing the first local medical society in 1821. Of special significance, Robertson initiated the use of quinine for malaria victims.

West Tennessee drew settlers once the Indian threat was removed. Memphis’s first physicians arrived in the 1830s. Two engaged in practice were Dr. Mark B. Sappington (a grandson of Nashville’s Dr. Sappington) and Dr. Wyatt Christian. In 1842 Sappington offered to vaccinate all of the city’s residents against smallpox. Christian represented Shelby County at a meeting called in 1830 to organize the Medical Society of Tennessee.

Many untrained healers practiced alongside physicians. Lay practitioners and the common people dispensing care to family members, especially in the South, were more likely to turn to Gunn’s Domestic Medicine than to physicians for help. Published in 1830, Gunn’s book recommended drugs imported from Europe such as mercury and opium, which were readily available at local mercantile stores, rather than those gathered from medicinal plants native to Tennessee. Patent medicines, promising cures in a single bottle for every ailment imaginable, rested comfortably beside mercury and opium on mercantile shelves. In the absence of physicians, settlers carried dog-eared texts containing remedies and traded recipes for concocting them, since treatment was administered at home.

By the 1830s botanical healing movements had gained substantial favor among the common folk. An emerging abhorrence to heroic treatment, consisting of blood letting, purging, and blistering, which had arisen in the 1790s from the pen of Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush, encouraged that interest. Samuel Thomson, an itinerant herbalist, provided the justification for using herbs in healing, proclaiming every man his own physician. Thomson had at least twenty-nine agents in Tennessee spreading his message.

As medical sects began to establish a grip on the American public, traditionally trained physicians attempted to organize to defend their legitimacy as purveyors of healing. On May 3, 1830, 47 physicians gathered in Nashville to form the Medical Society of Tennessee. Charter members of the new organization were drawn from the ranks of the reputedly best doctors in the state. East Tennessee provided 45 of the 151 named physicians, with 79 from Middle Tennessee and 27 from West Tennessee. On the appointed day, the attendees wrote by-laws and on the second day elected Nashvillian Dr. James Roane as the first president.

Despite physicians’ efforts to professionalize medicine, an informal 1850 census conducted in East Tennessee indicated that of 201 practicing doctors only 35 had graduated from a medical school. The others possessed professional training ranging from one course of medical lectures to no formal training whatsoever. Clearly, many of the physicians were self-proclaimed. Without licensing procedures, which did not become law in Tennessee until 1889, anyone could declare himself, or herself, a physician. Although the Medical Society of Tennessee had the power to confer licenses, rarely did anyone apply. Initially, the state society languished before physicians’ lethargy, geographical considerations, and the Civil War.

A promising development occurred in 1851, when the Medical Department of the University of Nashville opened. Physicians desiring a credible education no longer had to travel to Philadelphia or Kentucky to receive it. Enrollment swelled over the next decade until, in 1859, the school was the third largest in the United States. Three outstanding physicians on the medical faculty, Paul F. Eve, William T. Briggs, and William K. Bowling, guaranteed a propitious beginning for the new school. The Tennessee legislature relinquished operation of St. John’s Hospital, formerly an insane asylum, to the faculty of the new medical department. Successful from the beginning, the school grew to enroll 456 students in the 1859-60 session.

In Memphis, keen competition materialized between followers of Samuel Thomson and traditional physicians, and both founded their own medical schools in 1846. Regular physicians supported the Memphis Medical College, while Thomsonians favored the Botanico-Medical College.

Medical conditions on and off the battlefield during the Civil War were dismal. Dr. Samuel S. Stout, placed in charge of the Gordon Hospital founded by a ladies’ benevolent society in Nashville, declared the facility unsuitable and considered the women to be an interference. Stout reorganized the facility and wrested control from the ladies. Later when Stout was reassigned to Chattanooga and placed in charge of the Army of Tennessee’s hospitals, he found more of the same. Cleanliness varied considerably among hospitals. Nurses, who were untrained and in short supply, were drawn from the white and black population without regard to gender. Eventually female matrons were appointed to oversee laundry, bedding, food, and medicine in hospitals. Well-known Federal forces nurse Mary Ann Bickerdyke served as matron of Adams Hospital and Gayoso Hospital in Memphis. Confederate forces established twelve hundred hospital beds in that city, which Federal forces increased to five thousand when they took control in 1862. Nuns from the Sisters of Charity and Dominican nuns from St. Agnes provided nursing care.

Deplorable behind-the-line conditions for physicians attached to field troops included battlefields strewn with dead men and dead horses, and the smallpox, typhoid, and dysentery that raged among the soldiers. Without clear knowledge of where diseases originated or how they were spread, physicians labored against formidable odds.

The Civil War and postwar readjustments influenced the future course of professional medicine in Tennessee. The Memphis Medical College reopened briefly following the Civil War, but folded in 1872. The Botanico-Medical College in Memphis suffered a similar fate. The Nashville medical school remained open, but never recovered sufficiently after the war. The newly established Vanderbilt University forged an agreement with the University of Nashville’s medical department in April 1874 that shared the faculty between the schools. The winner in this arrangement was Vanderbilt, which eventually outshone the University of Nashville. Two years later, Dr. Duncan Eve, a son of Dr. Paul F. Eve, and Dr. W. F. Glenn founded the Nashville Medical College. Its faculty came from Vanderbilt and the University of Nashville. In 1879 the Nashville Medical College became the Medical Department of the University of Tennessee.

Several medical schools to train African American physicians opened in the late nineteenth century. In 1876 Meharry Medical College was created as the Medical Department of the Central Tennessee College. The school prospered under the adept guidance of Dr. George W. Hubbard. Coeducational from the outset, Meharry enrolled more women than any other medical school in the state. As white schools increased their enrollment of women, however, Meharry’s enrollment slipped, probably because of increasing expense. Still, Meharry graduate Dr. Mable Clottele Smith Fugitt served on the faculty of the University of West Tennessee College of Medicine and Surgery, a black medical training facility founded in Jackson that moved to Memphis in 1906 and closed in 1923.

The successive waves of cholera and yellow fever that afflicted towns and cities statewide were of considerable concern to the state’s general population throughout the nineteenth century. Memphis, pronounced by one contemporary writer as the filthiest town in America, often lived up to that unenviable reputation. Drinking water and sewage mixed with unimpeded freedom. Cholera, smallpox, and yellow fever made their way upstream by steamship, passing along the length of the Mississippi River. Even before the devastating epidemic of yellow fever in 1878, Memphis’s mortality rates in 1872 soared above other urban areas in the South and the nation. Finally city officials sprang into action and created a Board of Health. In less than ten years, the city’s death rate was cut by more than half.

The Tennessee State Medical Association (formerly the Medical Society of Tennessee) offered a bill to form a state Board of Health that passed in 1877, but as little more than a paper expression. No funds or authority accompanied the law. Rectified by an amendment the following year, the law granted power to quarantine and prescribe regulations with an appropriation of three thousand dollars annually. With additional pressure from the medical society, the general assembly passed a measure to gather and record vital statistics in 1881. Improved sanitation helped curb the effects of epidemics, yet tuberculosis and influenza, scourges of the twentieth century, took a significant toll.

From the 1870s through the 1920s, leading medical educators pressed for physician training reform. Initial unsuccessful reform efforts failed to stem the proliferation of low-grade proprietary medical schools. When Abraham Flexner published his report in 1910 on the condition of medical education in the United States and Canada, nine medical schools separated by race were in Tennessee. Knoxville had one white and one black medical school; Memphis had two white and one black medical schools, as did Nashville; and Chattanooga had one white medical school. Flexner recommended that the Vanderbilt University Medical Department and Meharry Medical College seize the responsibility of training physicians for the whole state. In 1911 the University of Tennessee, which had appropriated the Nashville Medical College and the Medical Department of the University of Nashville, moved its operation to Memphis and assumed the defunct facilities of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, and later those of the Memphis Hospital Medical College. At the same time, the school began to enroll women students. Lincoln Memorial University’s medical training facility in Knoxville transferred its students west when that institution closed in 1914.

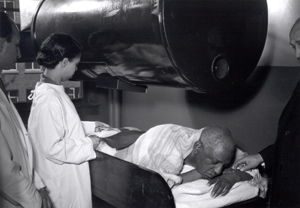

Hospitals, viewed at the beginning of the twentieth century as little more than a place to die, gradually moved to the forefront of medicine. Following military hospitals established during the Civil War came city- and county-supported hospitals such as the Memphis City Hospital, Knoxville General Hospital, Chattanooga’s Baroness Erlanger Hospital, and Nashville’s City Hospital. Over the years, major medical centers either absorbed or replaced those hospitals. The Commonwealth Fund of New York built the nation’s first modern hospital for a rural community, the Rutherford Hospital, in Murfreesboro in 1926-27. Over the years, major medical centers either absorbed or replaced the early major hospitals. The Hospital Corporation of America, later known as Columbia/HCA Healthcare Corporation, was founded in Nashville in 1968 and grew over the next three decades into the largest privately owned healthcare company in the country.

In recent years, the most critical problem in medicine has involved providing medical care for Tennessee’s citizens at a reasonable cost. Former Governor Ned Ray McWherter’s TennCare initiative, begun in 1993 to serve Medicaid and uninsured citizens, sought to solve that problem. The state dispensed medical care reimbursement through regional managed care organizations run by insurance companies. Some form of state-run managed-care program likely will endure as Tennesseans prepare for the future.

Suggested Reading

John C. Gunn, Gunns Domestic Medicine (reprint, 1986); Philip Hamer, The Centennial History of the Tennessee State Medical Association 1830-1930 (1936); Timothy C. Jacobson, Making Medical Doctors: Science and Medicine at Vanderbilt Since Flexner (1987); James W. Livingood, Chattanooga and Hamilton County Medical Society (1983); Samuel J. Platt and Mary L. Ogden, Medical Men and Institutions of Knox County Tennessee 1789-1957 (1969); Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein, Confederate Hospitals on the Move: Samuel H. Stout and the Army of Tennessee (1994); Marcus J. Stewart, William T. Black Jr., and Mildred Hicks, eds., History of Medicine in Memphis (1971); James Summerville, Educating Black Doctors: A History of Meharry Medical College (1983)