John Bell

John Bell was one of antebellum Tennessee's most prominent politicians and an acknowledged leader of the state's Whig Party. The son of a farmer and blacksmith, Bell was born in Davidson County and graduated from Cumberland College in 1814. After his admission to the bar in 1816, he opened a law practice in Franklin in Williamson County. A year later, his political career began with his election to the state Senate, but he declined to seek reelection after one term. Perhaps because he recognized the limitations of a provincial town for an ambitious youth, he moved to Murfreesboro, then Tennessee's capital, before finally settling in Nashville, the state's commercial center. By the time Nashville became the capital in 1826, Bell had established himself as one of the city's most prominent attorneys.

In 1827 Bell returned to politics and won the first of seven congressional terms in a bitter contest against former congressman Felix Grundy. He entered the House of Representatives as a supporter of Andrew Jackson, despite Jackson's endorsement of Grundy. Toward the end of Jackson's presidency, however, Bell worked with the administration's opposition. Never a member of the president's inner circle, Bell cultivated close connections with Nashville's mercantile community–solidified by his 1835 marriage to Jane (Erwin) Yeatman, the widow of one of the city's wealthiest merchants–and began to sympathize with the developing Whig Party's advocacy of federal government promotion of national economic development. At the same time, he apparently recognized that Jackson's preference for rival politicians would hinder his own aspirations. In 1835, although he still proclaimed loyalty to the administration, Bell accepted opposition support to win election over James K. Polk, Jackson's choice as Speaker of the House. Later that year he openly broke with the president when he became one of the leaders of the movement to elect Tennessee Senator Hugh Lawson White, rather than Democratic Party nominee Martin Van Buren, as Jackson's successor.

After White's loss in the 1836 presidential election, Bell successfully worked to move White's support into the national Whig Party, and the party ultimately rewarded him for his service with an 1841 appointment as secretary of war for the first Whig president, William Henry Harrison. Bell served only six months in the War Department before he and other cabinet members resigned after the party repudiated John Tyler, who had become president following Harrison's death. Returning to his law practice in Nashville, Bell spent the next six years watching political developments and waiting for the chance to return to public office. His opportunity finally came in 1847, when he agreed to serve a term in the state House of Representatives, where he gathered sufficient support to win election to the United States Senate.

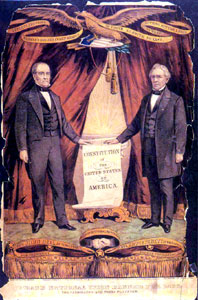

Reelected to a second term in 1853, Bell served in the Senate during the national debate over the expansion of slavery into new territories. Although a slave owner, Bell quickly distinguished himself as an advocate of compromise. The only senator from a southern state to vote against passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, in 1858 he defied instructions from the Democratic-controlled Tennessee General Assembly and voted against Kansas's admission to the Union as a slave state. By the latter date, the legislature had already elected a Democrat to succeed him in the Senate, but his reputation as a defender of the Union made him an ideal presidential candidate in 1860 for the hastily formed Constitutional Union Party. In a contest characterized by sectional division, Bell finished last among four candidates, but he won the second largest number of popular votes in the southern states and carried the electoral votes of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia.

When the lower South seceded after Abraham Lincoln's presidential victory, Bell at first urged Tennesseans to remain in the Union, and he met with the new president to encourage him to pursue a peaceful policy toward the South. After Fort Sumter and Lincoln's call for volunteers to put down the rebellion, Bell became convinced that the Republicans intended to impose a military dictatorship upon the South. He then reluctantly endorsed Tennessee's withdrawal from the Union. As the champion of a broken Union, Bell witnessed his political career come to an abrupt end. He avoided the Union army's occupation of Tennessee by moving to Alabama and later Georgia. After the war he spent his remaining years near the family's iron foundry in Stewart County.

Despite the oblivion of his later years, Bell had been among the most prominent southern politicians in the antebellum era. His career presents a reminder that Tennesseans were united neither behind Andrew Jackson's Democratic Party nor behind the extreme advocates of the defense of southern rights.

Suggested Reading

Joseph H. Parks, John Bell of Tennessee (1950)