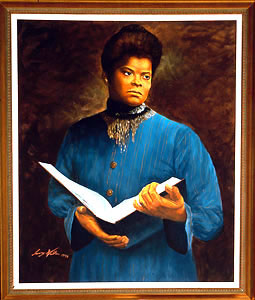

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, journalist, feminist, and civil rights activist, launched an antilynching campaign in the 1890s that made her one of the most outstanding African American women of the nineteenth century. The eldest of eight children born to James “Jim” and Elizabeth “Lizzie” Warenton Wells, she was born a slave in Holly Springs, Mississippi, on July 16, 1862. Orphaned by the yellow fever epidemic of 1878, Wells left Shaw University (now Rust College) and, at age sixteen, became a teacher in rural Mississippi to support her younger brothers and sisters.

Ida B. Wells moved to Tennessee in the early 1880s and taught in Shelby County before obtaining a position in the Memphis public schools. She challenged segregated public accommodations by filing suit in 1884 against the Chesapeake, Ohio and Southwestern Railroad after being forcibly removed from the first-class ladies’ coach. Although the circuit court ruled in her favor, awarding her five hundred dollars in damages, the Tennessee Supreme Court reversed that decision in 1887. Her eviction from the train launched Wells on a career in journalism. Writing under the pen name “Iola,” she published accounts of her experience in African American newspapers such as the New York Freeman and the Detroit Plaindealer. She presented a paper, “Women in Journalism or How I Would Edit,” at the National Press Association’s conference in Kentucky, and later became editor of the Evening Star. In 1889 she bought a one-third interest in the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight; two years later she became a fulltime journalist and editor of the Free Speech after the school board fired her for writing an editorial critical of Memphis’s inferior segregated schools.

In 1892 three African American grocers–Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart–were arrested, dragged from jail, and shot to death by a mob in the infamous “lynching at the Curve.” Outraged, Wells bought a pistol for protection, asserting that “one had better die fighting against injustice than to die like a dog or a rat in a trap.” (1) In her editorials, the young journalist urged African Americans to leave Memphis. She exposed lynching as a strategy to eliminate prosperous, politically active African Americans and condemned the “thread-bare lie” of rape used to justify violence against blacks. Her allegations incensed Memphians, particularly her suggestion that southern white women were sexually attracted to black men. While Wells was in Philadelphia, a committee of “leading citizens” destroyed her newspaper office and warned her not to return to the city.

Wells moved to New York, where she bought an interest in the New York Age and intensified her campaign against lynching through lectures, newspaper articles, and pamphlets. Works from this period include Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892); A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States, 1892, 1893, and 1894 (1895); and Mob Rule in New Orleans (1900). To make her antilynching crusade international, Wells lectured in Great Britain in 1893 and 1894 and wrote a column entitled “Ida B. Wells Abroad” for the Chicago Inter-Ocean. She also cowrote a pamphlet to protest the exclusion of blacks from the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

On June 27, 1895, Wells married a widower with two small sons, the prominent Chicago attorney Ferdinand L. Barnett, and they became the parents of four children. She bought an interest in the Chicago Conservator, founded and edited by her husband, and continued to write forceful articles and essays including “Booker T. Washington and His Critics” and “How Enfranchisement Stops Lynching.” Eventually, her militant views, support of black nationalist Marcus Garvey, and outspoken criticism of race leaders such as Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois embroiled her in controversies. After she extolled the accomplishments of Garvey, the U.S. Secret Service branded her as a radical.

After a brief retirement from public life following the birth of her second child, Wells-Barnett continued her campaign for racial justice, the political empowerment of blacks, and the enfranchisement of women. In 1898 she met with President William McKinley to protest the lynching of a postman and to urge passage of a federal law against lynching. After an outbreak of violence against blacks in Springfield, Illinois, she signed the call for a conference, which led to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. She distanced herself from the NAACP, however, because of differences with Du Bois over strategy and racial politics. In 1910 Wells-Barnett founded the Negro Fellowship League to provide housing, employment, and recreational facilities for southern black migrants. Unable to garner sufficient support for the League, she donated her salary as an adult probation officer, following her appointment to the office in 1913.

An early champion of rights for women, Wells-Barnett was one of the founders of the National Association of Colored Women. In Chicago she organized what became the Ida B. Wells Club; as its president, she established a kindergarten in the black community and successfully lobbied–with the help of Jane Addams–against segregated public schools. She also founded the Alpha Suffrage Club, which sent her as a delegate to the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s parade in Washington, D.C. Refusing to join black delegates at the back of the procession, she integrated the parade by marching with the Illinois delegation. Through her leadership, the Suffrage Club became actively involved in the election of Oscar DePriest, the first African American alderman of Chicago. Her interest in politics eventually led to Wells-Barnett’s unsuccessful campaign for the Illinois State Senate in 1930.

In 1918, in her unremitting crusade against racial violence, Wells-Barnett covered the race riot in East St. Louis, Illinois, and wrote a series of articles on the riot for the Chicago Defender. Four years later, she returned to the South for the first time in thirty years to investigate the indictment for murder of twelve innocent farmers in Elaine, Arkansas. She raised money to publish and distribute one thousand copies of The Arkansas Race Riot (1922), in which she recorded the results of her investigation.

Wells-Barnett continued to write throughout her final decade. In 1928 she began an autobiography, which was published posthumously, and she recorded the details of her political campaign in a 1930 diary. After a brief illness, Ida B. Wells-Barnett died on March 25, 1931, at the age of sixty-nine.

Suggested Reading

Miriam DeCosta-Willis, ed., The Memphis Diary of Ida B. Wells (1995); Alfreda M. Duster, ed., Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (1970); Paula Giddings, When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America (1984); Linda O. McMurry, To Keep the Waters Troubled: The Life of Ida B. Wells (1999)