Hunting

Tennessee’s early white settlers found bountiful supplies of wildlife, including deer, bear, elk, bison, and wild turkey; however, continued westward expansion rapidly depleted these populations. The last two reports of bison were recorded near Nashville in 1795; the last known Tennessee elk was killed in 1849. The unrelenting, one-two punch of habitat destruction and unregulated hunting, accelerating particularly in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, brought many other game animals to the brink of extinction.

Several restoration attempts with pen-reared animals were made in the 1930s, 1940s, and early 1950s. One of the largest was Grainger County’s Buffalo Springs Game Farm and Reserve, developed in the late 1930s by a partnership of the Civilian Conservation Corps, the National Park Service, the Tennessee Department of Conservation, and the Knox County chapter of the Tennessee Wildlife Federation. Most of them ultimately proved futile. In 1949 the establishment of the Tennessee Game and Fish Commission, precursor to the present Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, marked the beginning of wildlife management on a professional, scientific basis.

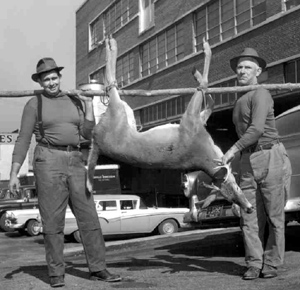

Restoration was achieved by live-trapping selected animals from the few remaining wild stocks and releasing them into unoccupied habitat. This slow process, coupled with protective regulations and reforestation efforts across the state, has seen native populations of white-tailed deer, black bear, and wild turkey–and the subsequent harvest by hunters–balloon to record numbers. In 1995, for example, hunters in Tennessee bagged 145,132 deer out of an estimated herd of 850,000, far more than likely existed in the early days of statehood.

The opposite trend occurred with rabbit and quail populations, upland species that thrive best in a farm environment. These animals were the mainstay of Tennessee hunters throughout the first half of the twentieth century and are still sought by thousands of small-game hunters today. Both species experienced an overall decline throughout the 1980s and 1990s, however, as small “patch” farmlands continued to disappear.

Deer, wild turkey, and squirrels rank among the most popular animals with Tennessee hunters. Hound enthusiasts also pursue raccoons and foxes statewide. In the Southern Appalachian and Cumberland Mountains, ruffed grouse, bear, and wild boar (offspring of European imports) are highly prized by hunters willing to stretch their legs.

Hunting for wildfowl, predominantly mourning doves and ducks, also is popular across the state. In the early fall, dove shoots over harvested grain fields are a southern social tradition, often replete with country music and dinner on the grounds. Later in the year native wood ducks, plus mallards, black ducks, teal, widgeons, scaup, and other migratory fowl provide excellent hunting in the wetlands along the Tennessee, Cumberland, Mississippi, Obion, Forked Deer, Hatchie, Wolf, and Duck River systems, as well as at famed Reelfoot Lake in northwest Tennessee. Local, nonmigratory populations of Canada geese have flourished in Tennessee since the mid-1980s and now provide excellent hunting opportunities, particularly in the middle and eastern portions of the state.

In the 1994-95 season 266,149 Tennesseans and 11,140 nonresidents purchased hunting licenses. Most hunting takes place on privately owned land. A network of sixty-four wildlife management areas (encompassing 1,320,000 acres) and thirty-one refuges (27,250 acres) is available to the public.