East Tennessee Iron Manufacturing Company

One of Chattanooga’s earliest industrial ventures, the East Tennessee Iron Manufacturing Company was a seminal force in the industrial development of the city and its surrounding area. Incorporated by the Tennessee General Assembly in 1847, the company benefited from the geological, technological, and economic conditions peculiar to the region.

Chattanooga is located in the Dyestone Belt, a physiographic region containing hematite ore deposits that, in the nineteenth century, were considered to have the greatest economic potential of any in the state. The Western and Atlantic Railroad selected Chattanooga as the terminus for its line from Atlanta, which was completed in 1850; the Nashville and Chattanooga connected the two cities four years later. As the company developed an iron industry in the fledgling city, the railroads provided the link between eager consumers and producers of raw and finished iron goods. Chattanooga’s potential as a boomtown rail junction also caught the eye of entrepreneurs seeking lucrative investments. The formation of the East Tennessee Iron Manufacturing Company gathered these diverse forces into a single purpose.

Several prominent Tennesseans served on the company’s board of directors, but Robert Cravens was the only principal partner with practical iron experience. Beginning in the early 1830s, Cravens successfully developed foundries, forges, and blast furnaces, becoming an accomplished ironmaster. He even built an experimental furnace in Roane County to measure the fuel efficiency of coke as compared to charcoal in the production of pig iron (raw iron derived from iron ore). Modern furnaces use coke as fuel, but in the mid-nineteenth century few furnaces in the entire country, and almost none in the South, used anything other than charcoal. Cravens’s innovations were applied to Bluff Furnace, the company’s most ambitious business venture in the 1850s.

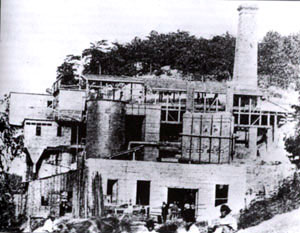

With the support of additional investors and Cravens’s conveyance of iron facilities, mills, real estate, and ore fields, the East Tennessee Iron Manufacturing Company became heavily involved in the iron industry. In 1853 the company opened a foundry and machine shop adjacent to the downtown rail yards; rail wheels and freight cars were evidently produced at the complex. In 1854 a new industrial plant was built on the banks of the Tennessee River; Bluff Furnace incorporated the natural topography of a high bluff and river transportation into its location and design. The bluff beside the forty-foot-high furnace stack afforded convenient access to the charging deck at the top of the furnace. There, massive quantities of charcoal fuel, iron ore, and a limestone flux were off-loaded from river barges and “charged” (placed in alternating layers) in the furnace interior. The furnace was then “put into blast” using preheated, compressed air to reduce the ore at a hotter, more efficient temperature. The furnace did not begin operation until 1856, when it produced 172 tons of pig iron in thirteen weeks.

In 1859 the main stack was torn down, and under the direction of northern ironmasters James Henderson and Giles Edwards, a new coke-fired furnace was erected in its place. Unique in the South, and rare elsewhere, the iron-clad cupola furnace stood on the cutting edge of iron technology. In May 1860 the new furnace produced 500 tons of iron before it ran out of coke. In November it resumed operations but soon succumbed to the problems generated by the political complications and demoralization of the workmen that accompanied the advent of war. Archaeological evidence at the site indicates that the furnace froze up in mid-blast and never operated again. It was demolished and its machinery recycled by other southern furnaces.

The Civil War brought an end to the East Tennessee Iron Manufacturing Company and its innovative iron furnace. But others, inspired by the Bluff Furnace example, continued in the tradition set by Robert Cravens. Chattanooga would grow into a town supported by heavy industry, one with roots reaching back to Bluff Furnace and the East Tennessee Iron Manufacturing Company.

Suggested Reading

R. Bruce Council, Nicholas Honerkamp, and M. Elizabeth Will, Industry and Technology in Antebellum Tennessee: The Archaeology of Bluff Furnace (1995)