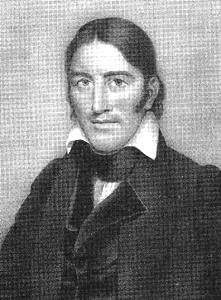

David "Davy" Crockett

David Crockett, frontiersman, Tennessee legislator and U.S. congressman, folk hero, and icon of popular culture, was an intriguing composite of history and myth. Both the historical figure who died at the Alamo and the legendary hero kept alive in the media of his day and ours, Crockett partly invented his own myth. History melted even more easily into legend as eager writers, editors, and producers provided an omnivorous public with an increasing number of remarkable tales about the heroic frontiersman and turned the flesh-and-blood David into the legendary Davy.

Born on August 17, 1786, in Greene County in East Tennessee, Crockett grew up with the new nation and helped it grow. He lived in Tennessee for all but the last few months of his life and promoted the gradual westward expansion of the frontier through Tennessee toward Texas. In his search for a better life for himself and his family, he participated in a process that we now call the American dream.

David was the son of John Crockett, magistrate, unsuccessful land speculator, and tavern owner, and Rebecca Hawkins Crockett. Preferring to play hooky rather than attend school, he ran away from home to escape his father’s wrath. His “strategic withdrawal,” as he called it, lasted about thirty months. When he returned home in 1802, he had grown so much that initially his family did not recognize him. He soon found all forgiven and reciprocated their generosity by working for a year to settle his father’s debts.

David married Mary “Polly” Finley on August 14, 1806, in Jefferson County. They remained in East Tennessee until 1811, when the Crocketts and their two sons, John Wesley and William, settled in Lincoln County. In 1813 they moved again, this time to Franklin County, where Crockett twice enlisted as a volunteer in the Indian wars from 1813 to 1815; following the wars, he was elected a lieutenant in the Thirty-second Militia Regiment of Franklin County. Soon after his discharge, Polly gave birth to Margaret, their third child; Polly died that summer. A year later, he married Elizabeth Patton, a widow with two children. The family moved to Lawrence County in the fall of 1817.

Although he served as a justice of the peace, Lawrenceburg town commissioner, and colonel of the Fifty-seventh Militia Regiment of Lawrence County, Crockett was relatively unknown before his 1821 election to the Tennessee legislature, representing Lawrence and Hickman Counties. Reelected in 1823, but defeated in 1825, he won election to the U.S. House of Representatives from his new West Tennessee residence in 1827. He campaigned as an honest country boy and an extraordinary hunter and marksman–someone who was in every sense a “straight shooter.” Reelected to a second term in 1829, he split with President Andrew Jackson and the Tennessee delegation headed by James K. Polk on several important issues including land reform and the Indian removal bill. Crockett was defeated in 1831, when he openly and vehemently opposed Jackson’s policies, but was reelected in 1833.

Notoriety gave Crockett’s image a life of its own. By 1831 Crockett had become the model for Nimrod Wildfire, the hero of James Kirke Paulding’s play, The Lion of the West, as well as the subject of numerous books and articles. In fact, Crockett claimed he was compelled to publish his 1834 autobiography A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee, which he wrote with the help of Thomas Chilton, to counteract the outlandish stories printed in Sketches and Eccentricities of Col. Crockett, of West Tennessee a year earlier. He clearly recognized the power of his popular image and sought to manipulate it for political gain. Anonymous eastern hack writers took up the more outrageous stories and spun out tall tale yarns for the Crockett Almanacs (1835-56). In their hands, the fictional Davy became a backwoods screamer. With the death of the historical Crockett at the Alamo in 1836, the floodgates opened for the full-blown expansion of the legend. Crockett could not only “run faster, -jump higher, -squat lower, -dive deeper, -stay under longer, -and come out drier, than any man in the whole country,” but he could save the world by unfreezing the sun and the earth from their axes and ride his pet alligator up Niagara Falls.

Touted by the Whigs as the candidate to oppose Jackson’s hand-picked successor Martin Van Buren in the 1836 election, Crockett was defeated in his 1835 congressional bid with the help of Jackson and Governor William Carroll. The election of Adam Huntsman, a peg-legged lawyer, temporarily disenchanted Crockett with politics and his constituents, prompting him to make the now-famous remark: “Since you have chosen to elect a man with a timber toe to succeed me, you may all go to hell and I will go to Texas.” His last letters spoke of his confidence that Texas would allow him to rejuvenate his political career and finally make his fortune. He intended to become land agent for the territory and saw the future of an independent Texas as intertwined with his own.

He and his men joined Colonel William B. Travis at San Antonio De Bexar in early February 1836. Mexican General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna arrived on February 20 and laid siege to the Alamo. Travis wrote that during the first bombardment, Crockett was everywhere in the Alamo, encouraging the men to fight and fulfill their duties. The siege of thirteen days ended on March 6, 1836, when Mexican troops overran the Alamo at about six o’clock in the morning. According to the eyewitness account in the diary of Lieutenant Jose Enrique de la Pena, Crockett and five or six other survivors were captured. Several Mexican officers asked that the prisoners be spared, but Santa Anna ordered them bayoneted and shot.

Many thought Crockett deserved a better fate, and they provided it, creating thrilling fictions from his clubbing Mexicans with his empty rifle until cut down by a flurry of bullets, bayonets, or both, to his survival as a slave in a Mexican salt mine. Clearly the present image of Crockett in American popular culture is the descendant of this tradition of Davy as the hero of romantic melodrama. From his characterization by Paulding as Nimrod Wildfire to that of Frank Mayo as author and star of the long-running play Davy Crockett: Or, Be Sure You’re Right Then Go Ahead, the legend was passed on through a series of silent and modern films that culminated in the portrayals of Crockett by Fess Parker in the well-known Walt Disney productions and John Wayne, who produced, directed, and starred as Davy in The Alamo. Nineteenth-century drama and twentieth-century film always presented a heroic, kind Crockett. Courageous, dashing, and true blue, this nobleman of nature protected his country and all who were helpless with equal fervor.

The Walt Disney-Fess Parker-inspired Crockett craze of the mid-1950s was without question the high water mark of the impact of the legendary Crockett. A media-generated event, it occurred at the moment when television first began to reach a mass market, and Disney launched his enterprise with the innovative premise that children represented a renewable audience. At the height of the craze, American youth drove their parents crazy with countless renditions of “The Ballad of Davy Crockett” and demands for coonskin caps and fringed deerskin jackets and pants. Department stores set up special Crockett sections to sell clothes and Crockett paraphernalia such as records, lunch boxes, towels, wallets, athletic equipment, baby shoes, and even women’s panties. Grosset and Dunlap’s sales for the book The Story of Davy Crockett increased to thirty times the ten thousand copies per year that had constituted normal sales before 1955. The total Crockett industry realized sales of approximately $300 million. And Disney was right about the recyclable nature of his market; today children meet Crockett on the Disney Channel on cable television.

Although Davy’s perennial best-seller status means that economic motives support the creation of different Crocketts, that fact need not tarnish our enjoyment of them. Neither should the Gordian tangle of man and myth obscure the essential unity of Crockett. Crockett, David and Davy, was frontiersman, congressman, blazing patriot, boisterous braggart, and backwoods trickster, with all the roles dissolved by a puckish good humor and recast into a single, fun-loving presence. The Crockett of history and culture is large and mirrors the ever-changing self-image of the United States. Invested in him–both as man and myth–are the hopes and beliefs, the virtues and values, and the shortcomings and triumphs of each generation of Americans who take him up as one of their heroes.

Suggested Reading

David Crockett, A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett (1834); Michael A. Lofaro, ed., Davy Crockett: The Man, the Legend, the Legacy, 1786-1986 (1985); James A. Shackford, David Crockett: The Man and the Legend (1956)