Clarksville

The county seat of Montgomery County and the second oldest municipality in Middle Tennessee, Clarksville is the state’s fifth largest city, with a population of 103,455. Established in 1784 by the North Carolina legislature as the seat of Tennessee County and named for Revolutionary War hero George Rogers Clark, the town was part of a reservation set aside by North Carolina to compensate its Revolutionary War soldiers.

Clarksville grew rapidly because of its access to the navigable Cumberland River and because of the rich Highland Rim soil that produced the acclaimed dark-fired tobacco. In 1788 the town was designated a tobacco inspection point to help ensure the quality of tobacco shipped to market. Consequently, the river town became an important trade center for its agricultural hinterland.

Following statehood in 1796 the fortunes of Clarksville improved with the rest of Middle Tennessee. The Clarksville Chronicle was established in 1808, and local resident Willie Blount was elected governor a year later. The transportation and market revolutions of 1815 to 1860 brought profound change to the nation and to Clarksville. In 1820 the steamboat first appeared at Clarksville, eventually turning the Cumberland and other navigable rivers into two-lane river highways, lowering transportation time and costs while vastly expanding the tonnage shipped. This promoted the building of more and better roads, extending Clarksville’s economic pull further into the countryside. Cave Johnson, a Democratic U.S. congressman, and Gustavus A. Henry, the local Whig Party leader, characterized the town’s vigorous political contests of this era.

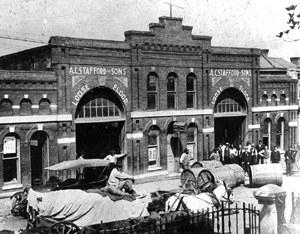

Clarksville’s economy, centered on its agricultural base in dark-fired tobacco, reached its pre-Civil War zenith in 1858. More than eighteen thousand hogsheads of dark-fired tobacco were shipped to international markets, returning more than $2.3 million. Clarksville’s type 22 tobacco became the most famous strain in the markets of England, France, Germany, and Italy. Individual enterprise in the sale of tobacco, however, gave way to large, consolidated tobacco companies, which maintained warehouses along the river and adjacent to the city’s developing railroad network.

The introduction of rail traffic in 1859-60 by the Memphis, Clarksville and Louisville Railroad, which opened a modern bridge over the Cumberland River, tied the city to larger transportation systems. Such access had great economic significance, but it also increased Clarksville’s strategic value in the Civil War. Union armies invaded the region in 1862 to grab control of the rail and river systems and to close production at pig iron furnaces in Montgomery and surrounding counties. Ironically, Clarksville residents initially had opposed secession, and former rivals Johnson and Henry both supported the Constitutional Union ticket of John Bell in the 1860 presidential election. Generally, residents seemed content to allow the Lincoln administration to govern in the spring of 1861, but events at Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s call for volunteers to squash the rebellion pushed residents to favor secession. Clarksville voters supported the secession vote in June 1861. Henry responded by serving in the Confederate Senate. Johnson withdrew from public affairs.

Recognizing Clarksville’s strategic importance, Confederate commanders directed the construction of two earthen forts, Fort Defiance and Fort Clark, at the confluence of the Red and Cumberland Rivers. Neither fort was fully completed or armed when a Federal flotilla under Flag Officer Andrew Foote approached Clarksville in February 1862. Confederate forces evacuated the forts and, after firing the Cumberland River railroad bridge, fled for Nashville. But citizens extinguished the bridge fire, saving this vital transportation link for local commerce, although later guerilla warfare along the line generally kept the line closed until 1865.

The Union occupation of Clarksville ended in September 1865, and in the following month both the tobacco market and the new First National Bank opened their doors for business. Normalcy did not immediately return, however. Conflicts over Reconstruction politics, rioting, and Ku Klux Klan activity marked the years 1865 to 1869. Whites consistently resisted black education and impeded whenever possible the activities of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Yet newly freed African Americans established such community institutions as St. Peter’s AME Church and made numerous attempts to establish public schools. A major commercial venture was established in 1868 when ex-Confederate Frank Gracey and his kinsman Julian Gracey opened a very lucrative mercantile business, F. B. Gracey and Brothers.

Agricultural trade remained the foundation of the local economy through the late nineteenth century. The town also was a center for the agrarian revolts of the time. The Grangers were introduced locally via the White’s Chapel Agricultural Protest headed by Joseph B. Killebrew, who was clearly the most important Clarksvillian since Johnson. Killebrew abhorred secession, freed his slaves, placed them on wages, and established a black school on his large farm. Killebrew supported the New South crusade and boosted public education and scientific agriculture. State superintendent of public instruction in 1872, Killebrew wrote the key work Introduction to the Resources of Tennessee in 1874. Congressman John House and U.S. Senator James E. Bailey, who succeeded Andrew Johnson in that office in 1877, were other prominent late nineteenth-century residents.

Racial conflicts persisted in the 1870s, and black businesses were especially hurt by the great arson fire of 1878 that destroyed fifteen acres of the central business district. Since the city’s population at this time was roughly equal in the numbers of whites and blacks, African American residents used their voting power to place several blacks in local government. John Page was a black city alderman while Jerry Wheeler was a black county commissioner. J. H. M. Graham, a black newspaper publisher, was elected to in the Tennessee General Assembly. The most prominent African American was Dr. Robert Burt, who opened a Clarksville clinic in 1904. Serving both blacks and whites, it evolved into the city’s only public hospital until the late 1940s. Without fanfare, both white and black doctors utilized Burt’s clinic. Mercifully, life can transcend race.

But reason could not submerge race completely. Nace Dixon, a black Republican city councilman, became active in the successful attempt to eliminate saloons in Clarksville. His activism for prohibition led the local Democratic organization to target him for defeat in 1907. Ward voting was secretly eliminated and replaced by citywide elections, effectively eliminating black political power in the name of progressivism.

During this same decade Clarksville was a focal point of the Black Patch War. As major producers of dark-fired tobacco, local planters and farmers were involved intensely in the efforts to break the monopoly of the American Tobacco Company. Farmers established the Eastern Dark-fired Tobacco Growers Association to organize and agitate for their interests. Extralegal night riders supported these goals from 1902 to 1912.

In 1919 Mrs. Brenda Runyon and others established the Women’s Bank of Tennessee in Clarksville. This was the first bank in the nation controlled entirely by women. Prominent residents during this era were U.S. Supreme Court Justice Horace Lurton; Perry L. Harned, educator and promoter of public schools; and Austin Peay, governor of Tennessee. Peay and Harned proved an effective team in creating a modern public education system, consolidating control of state administration in the governor’s office, and creating an improved state highway system.

The 1920s and 1930s witnessed a flowering of literature from writers either from the Clarksville area or then living in the region. Robert Penn Warren graduated from Clarksville high school in 1921. Caroline Gordon used Clarksville for the setting of much of her writing. She and her husband Allen Tate established a literary oasis at their home on the banks of the Cumberland River. Such important writers as Katherine A. Porter, Edmund Wilson, Robert Lowell, Herbert Agar, and Stark Young visited Gordon and Tate at their Clarksville home. Evelyn Scott, born Elsie Dunn, wrote the well-received autobiographical works Escapade and Background in Tennessee and the novel The Wave among other works.

In 1941 the War Department established Camp Campbell as a military training installation on 42,841 acres just north of Clarksville. Camp Campbell brought Clarksville into the vortex of wartime economic prosperity and created a cosmopolitanism in the community due to the increased contact between Clarksvillians and people from other parts of the country. When the camp became a permanent military installation, Fort Campbell, in 1950, residents knew that their future was fixed as part of the national scene. Fort Campbell remains the single most important force in the local economy and culture.

In 1954 Clarksville was one of the first communities in the nation to participate in the modern urban renewal programs of the federal government. The Civil Rights movement challenged public segregation throughout the city. Desegregation of education started when Austin Peay State College admitted its first black student, Wilbur Daniel, in 1956. But attitudes hardened, and when Dr. Robert McCan advocated integration, he was forced to resign from the city’s largest white Baptist church in 1960. Ironically, this happened in the same year that Clarksville resident Wilma Rudolph amazed the world with her multiple gold medals at the 1960 Summer Olympics. She received a public welcome from her hometown but still was unable to dine at a local chain restaurant.

The 1960s and 1970s produced school system consolidation, annexation of new areas into the city, continued economic expansion, and the rise of Austin Peay State College to university status. The completion of Interstate Highway I-24 in 1975-76 established a new, modern transportation link to replace an earlier reliance on the river and railroad. The town’s population, economy, and society have changed dramatically in the last twenty years as Clarksville seeks to assert its current marketing slogan, “Gateway to the New South.”