Civil Rights Movement

Like other states of the American South, Tennessee has a history which includes both slavery and racial segregation. In some ways, however, the history of the relationship between the races in the Volunteer State more closely resembles that of a border state than those of the Deep South. Although chattel slavery and the social attitude that undergirded it existed in Tennessee, slavery never achieved as much of a stranglehold upon the state as it did in most places of the South. Indeed, some parts of Tennessee reflected a hostility toward the institution, and portions of the state objected strongly to participation in a Civil War in which slavery played a prominent role. Nevertheless, the bloody clash between North and South did not alter most white Tennesseans’ belief in the racial inferiority of African Americans, no matter where they lived. Even as a border state, however, Tennessee witnessed its share of occasional violence and brutality, even lynching and race riots, and the state could take little pride in being the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan, founded in Pulaski shortly after the war.

Following the Civil War, Tennessee moved quickly to reenter the Union and, consequently, race did not muddy the political waters as dramatically as it did in the other ten Southern states that had left the Union in 1860-61. Even though legal segregation of the races did not appear immediately after the war, established social customs and tightly fixed racial etiquette dictated private and public contact between blacks and whites. White Tennesseans expected blacks to “know their place” and to stay within prescribed political, social, and economic boundaries. The violation of custom by blacks carried the terrible risk of embarrassment at least and even possible bodily harm. Black Tennesseans briefly glimpsed the sight of freedom in the early years following the war, but the appearance of more conservative forces on the political horizon soon dashed their bright hopes for the future.

Near the end of the nineteenth century, white racial attitudes in Tennessee and the country hardened. Various legislatures framed laws not only to regulate race relations but to control many aspects of the African American community. “Jim Crow” had arrived. In 1896 the U.S. Supreme Court gave legal sanction to segregation in the historic Plessy v. Ferguson decision that established the principle of “separate but equal.” For nearly sixty years Plessy displayed remarkably enduring strength, producing in Tennessee and in America a unquestionably separate but decidedly unequal society. Blacks, however, did not quietly succumb to racial oppression, and for the next half-century they carried out both overt and covert attempts to defeat Jim Crow. Activists such as newspaper publisher Ida Wells-Barnett of Memphis and other local leaders fought for black civil rights. Black Tennesseans who were able to vote used the ballot as a weapon in their own behalf, often punishing those who ignored the interests of the black community. Unfortunately, restrictions on the franchise stifled progress within the black community and delayed democratic equality in the state.

The World War II period helped to fuel a powerful movement in Tennessee and in other parts of the United States that moved the country away from Plessy and the discrimination that usually accompanied it. Participation in that conflict acquainted Americans with the visible results of racial and religious bigotry and its consequences for the country’s national fiber. The performance of black soldiers, including thousands of Tennesseans, during the war and the patriotic support of African Americans on the home front argued powerfully against an old system that kept racism alive and black persons second-class citizens.

Black Tennesseans contributed to the success of the war effort, and they also took part in the intellectual assault that led to the eventual demise of segregation. In Tennessee a number of public school teachers and college professors became involved with the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in an attempt to counter the effects of the shoddy scholarship that ignored black contributions to American history or that deliberately misrepresented the race. No scholar in Tennessee played a more crucial role in helping to bring about reform in race relations than sociologist Charles S. Johnson of Fisk University. Johnson came to Fisk in 1927, established the Race Relations Institute in 1934, and became the university’s president in 1937. He moved quietly but forcefully in his approach to the race problem. His research efforts and conferences, designed to bring blacks and whites together, had a meaningful impact on racial attitudes in Tennessee and in other parts of America where committed reformers worked for good race relations.

The new spirit generated by World War II and the efforts of scholars such as Johnson brought about some social changes in Tennessee before the mid-1950s. Although African Americans in the Volunteer State chipped away doggedly at the edifice of Jim Crow, white attitudes changed slowly. Blacks waged a vigorous and persistent attack upon racial oppression through a number of self-help and protest organizations including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The NAACP and a number of local groups worked to equalize teacher salaries, to abolish segregated public accommodations, and to invalidate the hated Tennessee poll tax, which restricted the black franchise in several parts of the state. Where blacks did have the ballot, they often used it wisely to exact gains from urban politicians in Nashville, Knoxville, and Chattanooga. In Memphis blacks represented a powerful part of the political machine that controlled the city for many years. Ironically, their activity provided whites with an argument against the poll tax as well, as opponents of the political leadership in Memphis during the era of Edward H. “Boss” Crump alleged that his machine paid poll taxes for blacks and dictated their vote. Some Tennessee blacks found themselves at odds with members of their own race because of the close alliance between some Memphis blacks and Crump, who often flexed his muscle in statewide politics.

Segregation was a strong and resilient social and political force. In the 1950s Jim Crow remained intact, despite the new spirit that prevailed, and its death would come painfully, slowly. More than ever, black Tennesseans now questioned their mandated role in society. They sometimes walked off jobs or went on strike when treated unfairly in employment, challenged private citizens and municipalities in court for alleged wrongs, and pressured the state to abolish racially exclusive laws. The Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) further emboldened black Tennesseans, for it not only mandated desegregation of the public schools, but it also destroyed the props that gave support to racial segregation and discrimination in general. No other development in the social sphere threatened to create as much possible disruption as the case that turned Plessy upside down and abolished the legal principle of separate but equal.

Brown generated hostility among many white Tennesseans and other southerners who visualized chaos within their land. To them the case meant not only desegregated schools but also social integration throughout society; and increased social contact between the races on equal terms, they believed, would lead inevitably to interracial courtship and even marriage between the races. A haunting fear gripped those who believed in the old order. To insist that young white children become pawns in a broad social experiment proved unacceptable to most white Tennesseans, who had never known anything other than a society guided by the Plessy decision. Federal court intervention, they said, had gone too far in the lives of the people, had exceeded constitutional limits by infringing upon the rights of the states, and ultimately threatened to sacrifice the well-being of their children.

For Tennesseans, then, Brown represented more than a mere legal abstraction. Although the case disturbed most white citizens, they moved cautiously in their response to the decree. The city of Knoxville provided a good index to the attitudes of whites in the state at that time. A city of less than 10 percent black population in 1954, some observers regarded Knoxville as the least racially sensitive of the state’s largest cities. An opinion poll in 1958, however, revealed that 90 percent of white citizens strongly disapproved of desegregation. It showed further that not a single white person of the 167 polled would agree to enrolling even one white child in a black school, and nearly 72 percent would oppose sending a black child to a white school. Ninety-four percent of those polled opposed sexually and racially mixed classes. Such figures were a powerful commentary. Ironically, however, those whites who had defended Plessy as the law of the land now found themselves painted into a legal corner in a country that supposedly honored the rule of law.

For blacks, desegregation of the schools pointed toward progress in education, but Brown also brought some unexpected problems. Many black Tennesseans, including a number who had fought relentlessly to overthrow segregation and racism, had not pondered how thoroughly their lives had become culturally and economically interwoven with the African American school. As an institution, only the family and the church were more central to black community life. Because of its social attractions and its many extracurricular activities, the black school served as a powerful agent for racial cohesiveness. Although many African Americans in Tennessee applauded the death of Jim Crow in education, they lamented the passing of special school activities that had once fostered a vital sense of community among them–athletic contests, choral renditions, dramatic productions, and other functions. Desegregation raised in an unexpected and striking manner not only educational questions, but cultural ones as well.

Despite white dissatisfaction with Brown, desegregation proceeded with less recalcitrance and violence than in most other states of the South. But violence was not totally foreign to the state, since public schools in Nashville and Clinton did experience damage to two of their schools from bomb blasts. In the case of Clinton, tensions remained high until Governor Frank G. Clement called out the National Guard to restore calm. Although most Tennessee localities, and the state government itself, connived at ways to slow desegregation, they faced a losing battle. Various plans to stall desegregation or to delay implementation of court orders to achieve integration ultimately failed when they confronted federal action, the resistance of the black community, and a state newspaper press that, by and large, encouraged obedience to the law.

Some citizens hoped that the institution of cross-town busing would offer a panacea for desegregation of the public schools, especially in urban areas of Tennessee. They were wrong. By the mid-1990s opposition to busing still remained strong, and some cities, such as Nashville, had begun to study other approaches to desegregation. Paradoxically, integration had made some of its most notable advances where persons had least suspected–rural areas and where hard-core racial attitudes had once prevailed. Rural white children had ridden buses for long distances to school for many years, and the debate over busing took on a slightly different meaning in places where an entire surrounding area constituted a “neighborhood.”

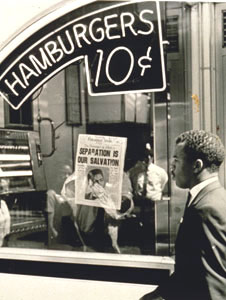

If desegregation of schools offered Tennessee a difficult challenge, so did direct-action protest techniques to abolish segregation in public facilities. Through the efforts of young black students, especially in Nashville at Tennessee State University, Fisk University, Meharry Medical College, and American Baptist Theological Seminary, the state would bequeath to the national civil rights campaign valuable lessons in protests while raising to prominence a number of notable young black leaders. In Knoxville African Americans and a small number of white protesters would also wage a determined campaign against public Jim Crow. Before the mid-1950s black Tennesseans had already begun to use their institutions as vehicles to fight the forces of segregation. By the time of Brown, then, a social consciousness, anathema to inequality and the idea of black inferiority, existed in the state among African Americans. In the 1960s–during a period often alluded to as the “Movement” days of civil rights–black college students and their allies aided reform with an idealistic crusade that found segregation intolerable and public demonstrations a legitimate technique for battling societal wrongs.

The Nashville civil rights demonstrations stood out among the most noted sit-in activities in Tennessee. But in other cities of the state during the sixties and early seventies, indigenous black leadership contributed to the abolition of societal restraints that made democracy more real for many Tennesseans. Significantly, the movement in Nashville developed from a rather old political base and institutional arrangements that gave protest more of a possibility of success.

Sit-ins by African Americans, of course, predated the modern Civil Rights movement that followed Brown. In Nashville, they owed much of their success to effective leadership of the black clergy. Although historians now realize that a much larger leadership base existed throughout Tennessee than was once known, two persons in particular stand out in the history of protest in the city and the state–Kelly Miller Smith and James Lawson. Smith was the youthful pastor of First Baptist Church, Capitol Hill. A handsome, articulate, charismatic figure, he had a powerful appeal to both young and old. In early January 1958 Smith and other black activists organized the Nashville Christian Leadership Conference (NCLC), an affiliate of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), with which Smith was already affiliated. King, of course, was the acknowledged leader of the Civil Rights movement from the mid-1950s until his untimely death at Memphis 4 April 1968. The NCLC and SCLC had as their ultimate objective a frontal attack on the immorality of discrimination through the unification of ministers and laymen in a common effort to bring about “reconciliation and love” in a racially just society.

Lawson, another young clergyman, worked to hone the technique of nonviolent resistance that finally triumphed in Nashville and other places in Tennessee, as well as all over the South. He had come south from Ohio to attend the Divinity School at Vanderbilt University. A serious student of nonviolence who had spent time in India, Lawson began conducting workshops in 1958 at Smith’s First Baptist Church. As he and Smith developed a strategy for social action through NCLC, they recognized that the city of Nashville could serve as an important laboratory for testing nonviolent protest methods and become a model for other such activities. Lawson knew that segregated society was vulnerable to the power of a grassroots movement if participants willingly sacrificed and suffered to defeat the evil of injustice. When Vanderbilt University ordered Lawson to cease his activity or face suspension, he persevered, and the university dismissed him.

During the later part of 1959 the NCLC commenced its direct-action campaign against downtown stores with two so-called test sit-ins. When whites-only establishments refused blacks service, youthful demonstrators left the facilities after discussing with management the injustice of segregation and their denial of service. What these early public efforts demonstrated was the clear presence of discrimination in the city of Nashville. By January 1960 Smith, Lawson, and student protesters had decided to launch a full-scale, nonviolent attack against businesses that discriminated against blacks if they did not voluntarily alter their policies. Before the students could act, however, other protesters in Greensboro, North Carolina, initiated sit-ins in that city which precipitated demonstrations in other southern cities. Leaders of the Nashville movement now decided to move decisively. Led by Diane Nash, John Lewis, James Bevel, Cordell Reagon, Matthew Jones, and Bernard Lafayette, students from the city’s black colleges began more intense sit-in activity that led in May 1960 to the initial desegregation of some Nashville businesses. A number of factors accounted for their success. Undoubtedly the students’ determined and courageous efforts played a pivotal role in tearing down restrictive racial barriers, but a highly effective economic boycott of downtown Nashville stores by the black community also had a measurable impact. Furthermore, the city’s mayor, Ben West, openly acknowledged that the obvious immorality of discrimination helped to create a more moderate climate following violence against the students and some other black citizens.

Other cities in Tennessee also struggled with changes on the civil rights front in the 1960s and 1970s. Indigenous leadership in Knoxville produced considerable civil rights activity in that East Tennessee city. After black citizens failed to negotiate successfully the end to segregated public facilities, a protest movement led by students at Knoxville College and Merrill Proudfoot, a white minister at that institution, set out to change laws and customs in a city that prided itself on “healthy” race relations. A broad-based movement, the Knoxville campaign drew support from a large number of African Americans who lived in the city, a sizable number of white moderates, and city officials willing to listen and act with reasonable restraint. Following the initiation of sit-ins in June 1960, white city leaders and politicians of Knoxville convinced businessmen to desegregate by mid-July.

The courageous acts of young black demonstrators and their supporters united the black community in Tennessee and challenged the consciences of those whites who casually–sometimes unthinkingly–accepted the laws and customs of contemporary society. The African Americans of Tennessee made an important contribution to the reform tradition in America by assisting the birth of a powerful social movement that changed the country, finally fulfilling the promise of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States, and substantiated the faith in individual growth and progress that so many other persons had sought in Tennessee. Tennesseans did much to foster the idea of nonviolent protests during the era of Martin Luther King; how ironic it is that the movement era came to an end with the assassination of King in April 1968, when James Earl Ray’s bullet ripped through his body.

The four decades since Brown have produced measurable progress in black civil rights in Tennessee and the nation. The country saw the passage of a civil rights bill, a voting rights act, and housing legislation, and the federal government has instituted a number of social programs designed to redress past grievances. In 1952 the courts forced the state to admit its first blacks to its graduate, professional, and special schools. Nine years later, the University of Tennessee admitted undergraduates to its Knoxville campus, although six blacks were already matriculating at the institution’s Nashville campus, which under court order later became part of previously all-black Tennessee State University. By 1965 the state could announce that all seven of its institutions of higher learning had technically integrated, and that color was not a precondition for admittance. High school graduation rates, too, were encouraging. At the time of the first major sit-in in Tennessee, less than 9 percent of African Americans had finished high school, but by the mid-1990s that figure exceeded 40 percent.

Strides in the political arena also proved impressive. In 1964 Tennessee elected its first black state legislator since the late nineteenth century, A. W. Willis Jr.; two years later the first African American woman, Dr. Dorothy Brown, won a seat in that body. By 1993 twelve African Americans sat in the legislature, and a total of 168 blacks served in various political positions in a state where 16 percent of its citizens were African American. In January 1992 black votes in Memphis helped to catapult into the office the city’s first black mayor, Willie W. Herenton. In the fast-growing metropolis of Nashville, an African American, Emmet Turner, earned the right to head the Metropolitan Police force in 1996.

In recent years, however, disturbing signs have appeared on the civil rights horizon. Despite recognizable progress, overcoming the past effects of discrimination and the achievement of full rights of citizenship remains a daunting task for African Americans. A number of programs designed to aid blacks, such as affirmative action, faced biting criticism in the mid-1990s. Notable discrepancies still existed between black and white incomes, and the federal courts threatened to dilute the effect of black political power with some of their decisions. As late as July 1996 the United States Commission on Civil Rights noted that Tennessee was sitting on “powder kegs” of tensions which could ignite into violence.

The Civil Rights Commission did not misread the times. But it may not have accounted for the considerable number of blacks and whites who wanted to create a better Tennessee, citizens who had the determination to fight the racial conservatism that threatened to damage the state and its reputation. Opinion polls bore out the contention that most Tennesseans did not want to overturn the fundamental changes made since Brown or to return to the ugly days of harsh segregation. But it was hard for many of them to make the personal or political sacrifices necessary to adjust the wrongs of the past. Yet a desegregated, pluralist society remained a healthy ideal for most Tennesseans, especially for those born in the post-Brown era. In the words of one hopeful native who lived through the era of segregation, the state has moved “too far to turn back.” That optimism, more than anything else, characterized the spirit of the African American community at the time of the state’s Bicentennial. It also registered the hope of more than a few white Tennesseans of good will who had come to decipher the real meaning of democracy, justice, and fair play.

Suggested Reading

Cynthia G. Fleming, “We Shall Overcome: Tennessee and the Civil Rights Movement,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 54 (1995): 232-45; Hugh D. Graham, Crisis in Print: Desegregation and the Press in Tennessee (1967); Lester C. Lamon, Black Tennesseans, 1900-1930 (1977); Merrill Proudt, Diary of a Sit-in (1990); Linda T. Wynn, “The Dawning of a New Day: The Nashville Sit-Ins, February 13-May 10, 1960,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 50 (1991): 42-54