Battle of Nashville

The battle of Nashville, fought December 15-16, 1864, continued the destruction of the Confederate Army of Tennessee that had begun when it suffered devastating casualties at Franklin. After that engagement, army commander John Bell Hood faced limited options. A withdrawal would further dishearten the army, and Hood rejected his former notion to bypass Nashville and head northward. The high toll at Franklin prevented him from seriously contemplating an assault at Nashville, another earlier scheme. Hood opted instead to bring his army to the city’s outskirts and await an attack from the Federals, hoping to counterattack if the enemy left an opening.

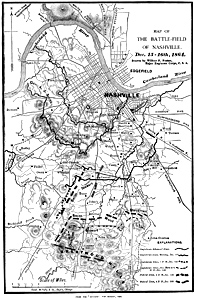

The Confederates moved north from Franklin in early December and established a five-mile defense line. There were serious flaws in the position, since it did not come close to covering all the major roads leading from the city. The army was situated so that Frank Cheatham’s corps occupied the right near the Nolensville Pike, Stephen D. Lee’s corps the center astride the Franklin Pike, and A. P. Stewart’s corps the left, crossing the Granny White Pike and bent back near the Hillsboro Pike. In spite of their efforts to entrench and strengthen their defenses, the Confederates were vulnerable on both flanks.

Hood’s adversary, General George Thomas, enjoyed several compelling advantages. His Federals occupied extraordinarily strong works, since Nashville by late 1864 was one of the most heavily fortified cities in America. Although it had taken time for Thomas to amass his force, by mid-December he had over fifty-four thousand effectives on hand at Nashville, well over twice Hood’s numbers. Thomas’s force represented a conglomeration of disparate elements, including the Fourth Army Corps from the Army of the Cumberland and John Schofield’s Twenty-third Army Corps, both sent back by William T. Sherman before he began the March to the Sea. There were also twelve thousand rugged troops led by Andrew J. Smith recently arrived from Missouri. Thomas intended to use these battle-hardened units to smite Hood. He concocted a plan to keep Cheatham on the Confederate right occupied, then concentrate the bulk of his army against Stewart, wheeling around the Southern left flank with overwhelming numbers.

Bitterly cold and inclement weather pushed into Middle Tennessee the second week of December, forcing Thomas to delay his attack. This sensible decision did not sit well with Union officials in far-off Washington or with Ulysses S. Grant in Virginia, who worried about Hood’s lingering presence in Middle Tennessee. Grant seriously contemplated replacing Thomas, but a thaw set in on December 13 and allowed Thomas to convene his officers and issue final orders for offensive operations.

Union troops under James Steedman moved out against Cheatham early on the morning of December 15. Bitter fighting erupted when Cheatham’s veterans discerned that black soldiers made up a portion of the Federal assaulting party. Although Steedman suffered heavy casualties, he effectively neutralized Cheatham while the main Yankee blow fell on Stewart. Although Stewart’s men resisted valiantly, they were outnumbered ten to one, and the massive pivot devised by Thomas threatened to crush the Confederates. Hood sent reinforcements, first from Lee and then from Cheatham, but relentless pressure forced Stewart back towards the Granny White Pike.

After dark Hood ordered a withdrawal nearly two miles to the south and aligned his men in a more compact position. Cheatham replaced Stewart on the Confederate left. Thomas for his part had no intention of abandoning his plans and decided to continue with his successful tactics the next day. He did modify his strategy to attempt an envelopment of both Confederate flanks, however. On December 16, Thomas impatiently awaited as his units, somewhat scattered and out of position, sorted themselves out. He grew increasingly frustrated at Schofield’s reluctance to attack, but Union artillery pounded the makeshift Southern defenses before the infantry assaulted. When they finally did so, Cheatham’s defenses crumbled. A pivotal salient occupied by the Twentieth Tennessee held out against a fierce Union artillery barrage from three directions, but Colonel William Shy and his men atop the hill were practically obliterated when Union infantry overran the summit. The remainder of Cheatham’s left collapsed, and the panic extended to Stewart’s troops in the center.

Only a skillful defense by Stephen D. Lee prevented Thomas from achieving his goal of encircling the Confederates and annihilating them. Lee pulled his corps back to the Overton Hills and managed to stave off the Federals. Lee continued his rear guard actions the next day, while the rest of the army passed through Franklin. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry and infantry fragments from eight brigades led by General Edward C. Walthall covered the withdrawal. Union cavalry persistently hounded the retreat until the Confederate survivors managed to cross the Tennessee River. Thomas called off the pursuit on December 29.

Hood lost some six thousand men at Nashville, many of them captured when they failed to make good their escape from the battlefield. Union casualties were just over three thousand. Tennessee historian Stanley Horn entitled a 1956 book about the campaign The Decisive Battle of Nashville, and Horn’s work is aptly titled when one considers that Thomas narrowly missed destroying Hood’s entire force. Yet Federal success at Nashville was aided tremendously by the earlier action at Franklin, which had demoralized many Southerners and decimated Hood’s best combat units. Psychologically devastated by the losses at Franklin and unwilling to be sacrificed at Nashville, many of Hood’s most courageous veterans broke and fled there.

The result of Hood’s Tennessee campaign, which began with such heady optimism in the fall, was the near-total disintegration of his army. The remnants of the army finally halted at Tupelo, Mississippi, but large numbers of men deserted along the way and others did so shortly after reaching Mississippi. Hood asked to be relieved on January 13, and Richmond authorities accepted the request. Two fatal decisions by Hood, the first to launch a frontal assault at Franklin, and the second to await Thomas at Nashville, doomed his army in the campaign. And George Thomas belied his reputation as a slow, stolid commander by delivering a well-conceived knockout blow at Nashville.

Suggested Reading

Stanley F. Horn, The Decisive Battle of Nashville (1956)