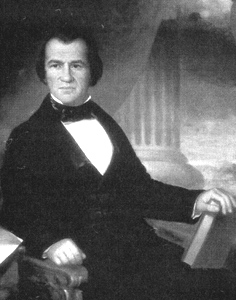

Andrew Johnson

Born in a log cabin on December 29, 1808, in Raleigh, North Carolina, Andrew Johnson knew abject poverty and personal tragedy almost from the very beginning of his life. Jacob Johnson, Andrew’s father, a landless and illiterate worker in Raleigh, died unexpectedly a few days after Andrew’s third birthday. At ten years of age, Johnson was apprenticed to work for James J. Selby, a tailor. In that shop, he learned two valuable lessons: how to perform the tailor’s craft and how to read. After five years in Selby’s shop, Johnson ran away from Raleigh, but he returned some two years later in an unsuccessful attempt to make peace with Selby. In 1825 or early 1826 Johnson again left, heading west to seek a better fortune.

He wandered to Mooresville, Alabama, and then to Columbia, Tennessee, and secured employment in tailor shops at both places. After a few months, however, Johnson returned to Raleigh and escorted his mother and stepfather Turner Doughtry to Tennessee. They eventually arrived in Greeneville in September 1826. There Johnson found work in a tailor shop, and, more importantly, he found Eliza McCardle. In the spring of 1827 the two teenagers (Johnson was eighteen and Eliza sixteen) married and made Greeneville their permanent home.

Two years later, twenty-year-old Andrew Johnson was chosen alderman, a post to which he was reelected several times, and in 1834 he became Greeneville’s mayor. Meanwhile, his tailoring business prospered, and his family increased to include two daughters and two sons. As a consequence Johnson purchased a tailor shop and a fine brick residence. Once he learned to write, Johnson became increasingly absorbed in intellectual pursuits as he prepared himself for more impressive and prestigious areas of public service.

In 1835 Johnson successfully ran for a seat in the lower house of the state legislature. At this point in his early political career he generally maintained political independence while leaning toward the newly emerging Whig Party. In fact, he backed Hugh Lawson White for president in 1836. His refusal to support internal improvements legislation favored by his constituents, however, cost him reelection in 1837. Two years later, Johnson regained his legislative seat. By this time, he had made an irrevocable commitment to the Jacksonian Party. Democrats named him to be one of the two state at-large presidential electors in 1840, and Johnson campaigned throughout Tennessee. Subsequently, he sought and won a state Senate seat the next year. But after three legislative terms, Johnson looked for new challenges.

He found them in the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served for ten years, 1843-53. Here he first introduced his famous Homestead Bill in the spring of 1846 and persisted until the House (but not the Senate) finally approved it in 1852. He sparred with President James K. Polk over patronage, supported the Compromise of 1850, and introduced constitutional amendments to provide for the direct election of the president and U.S. senators. During his tenure as a representative, he bought a larger house in Greeneville. In 1852 his fifth child, Andrew, was born; in that same year, the Whig-dominated legislature redrew the congressional districts to make Johnson’s reelection nearly impossible.

Faced with this reality, Johnson made a successful race for governor, and he was reelected in 1855. The governor’s office was weak by design, and Johnson accomplished very little, other than an increase in the revenues to support public schools. His principal achievement was to gain extensive public exposure, though, and thereby enhance his future career.

In the fall of 1857, the legislature’s choice of Johnson as U.S. senator surprised few. Once in the Senate, he immediately proposed his Homestead Bill, and he reintroduced it two years later. The bill finally emerged from both houses of Congress in late spring 1860, only to be vetoed by President James Buchanan–much to Johnson’s dismay. That year’s real excitement emanated from the presidential campaign, which involved four political parties. Johnson had flirted with the possibility of his own nomination, but the breakup of the Democratic Party at the Charleston convention had ruined those plans. Johnson campaigned for John C. Breckinridge, the Southern Democratic candidate, but the state went for John Bell, the Constitutional Union nominee.

In the wake of Abraham Lincoln’s election and amid threats of secession, Johnson returned to Washington. A few days later he delivered his famous speech against secession, in which he staked out his claim as a Southern Unionist. In a February 1861 referendum, Tennessee voters refused to endorse a secession convention call, yet Johnson knew he had to return home to fight against the surging tide of secession sentiment. He finally left in April, the month the Civil War began.

Back in East Tennessee, Johnson quickly allied with former political opponents such as Thomas A. R. Nelson, William G. Brownlow, Horace Maynard, and others who shared his strong support of the Union. Accompanied by these new friends, he toured the region and railed against secession and the Confederacy. After the June referendum, in which Tennessee voters embraced secession, though, a fearful Johnson hastily left the state and made his way into Kentucky and eventually back to Washington.

At that juncture he could scarcely have imagined his next assignment: military governor of Tennessee. After the Federal capture of Forts Henry and Donelson, followed by the occupation of Nashville (all in February 1862), President Lincoln sent Johnson to Tennessee for the purpose of restoring civil government and bringing the state back into the Union. Johnson arrived in Nashville in late March, and for the next three years, he struggled to accomplish this goal. In the process, he was often ruthless, dictatorial, accommodating, and strongly pro-Union. He arrested and imprisoned newspaper editors, local officials, and clergymen–anyone deemed to be a threat. But Federal and Confederate military activities in Tennessee had as much bearing upon Johnson’s role as governor as anything else. Indeed, both his office and his person were jeopardized from time to time by Confederate successes in the Middle Tennessee area.

The slavery question drove a wedge between the state’s Unionists, and Johnson eventually took a stance in favor of abolishing slavery, while the more conservative Unionists refused to do so. This schism also hampered the governor’s efforts to restore civilian government. Moreover, Johnson set forth more stringent loyalty oaths than Lincoln required, further alienating substantial numbers of Unionists–particularly at the time of the 1864 presidential campaign.

Johnson, needless to say, had more than a passing interest in the election; after all, Lincoln had placed him on the ticket as the vice-presidential nominee. In the victorious campaign’s aftermath, however, Johnson still had some unfinished business, namely, the establishment of civilian government in the state. Accordingly, he sanctioned a call for a January 1865 convention of Unionists. This unofficial Nashville gathering established dates for a referendum to abolish slavery and an election of gubernatorial and legislative officers. By late February, Johnson could delay his departure no longer if he wanted to arrive in Washington for the inauguration ceremonies. But the question of the readmission of Tennessee remained unresolved.

This longtime Democrat and resident of a Confederate state arrived in town to be sworn in as vice-president. Johnson’s apparent intoxication that March day stirred negative reactions, but not for long. Six weeks later, on the night of April 14, an assassin’s bullet ended Lincoln’s life. The next morning, Johnson was sworn in as the seventeenth president.

The stunned nation expectantly awaited Johnson’s leadership. He did not disappoint; indeed, the next several months constituted his “finest hour.” With Congress adjourned, Johnson had a free hand, and he took advantage of the situation. In May, for example, he extended amnesty and pardon to all ex-Confederates who took an oath of allegiance (except for those who fell under fourteen different exemptions). Moreover, he appointed provisional governors for seven of the former Rebel states. Throughout the summer and fall months, these states went about the business of holding elections and constitutional conventions. Meanwhile, Johnson granted thousands of individual pardons to repentant ex-Confederates. When Congress convened in December, the president bragged that the restoration of the southern states had been accomplished.

But Congress had different ideas. Its members ushered in 1866 with two significant measures: the Freedmen’s Bureau bill and the Civil Rights bill. Johnson vetoed both and thus assured that the year would be one of developing tension between the executive and legislative branches. Congress also approved the Fourteenth Amendment, but the president openly discouraged southern states from ratifying it. Ironically, his home state of Tennessee accepted the amendment (all other Confederate states rejected it) and thereby successfully gained readmission to the Union in July 1866. This enabled Johnson’s son-in-law David Patterson to claim his seat in the U.S. Senate and permitted Tennessee to escape Reconstruction.

If 1866 was a period of developing tension, the following year was one of open warfare between the president and Congress. Johnson chose to veto every major piece of legislation, including the three Reconstruction bills, the Tenure of Office act, and the District of Columbia Franchise law. Congress had no problem overriding these vetoes. Johnson fought back in the summer of 1867 by removing two of the five district commanders and by suspending Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. These actions fueled Radical intentions to get rid of the president.

Not surprisingly, in 1868 the House voted to impeach Johnson, and the Senate convened to hear the case against him. The chief charge revolved around the president’s alleged violation of the terms of the Tenure of Office act (by the removal of Stanton), but the real issue was political power. Eventually, in May, the Senate acquitted Johnson of the impeachment charges, but by then he was a greatly diminished leader. Yet he continued to veto congressional measures, including the admission of seven ex-Rebel states that had finally ratified the Fourteenth Amendment and sought to reenter the Union.

Even in his dark moments, Johnson clung to the unrealistic hope that he might be nominated for president by the Democratic Party in July. But Democrats named Horatio Seymour to be their standard-bearer, and Republicans rallied around General U. S. Grant. All knowledgeable persons accurately predicted Grant’s victory in November. Meanwhile, Johnson simply marked time as he awaited the end of his troubled presidency in March 1869.

Cheered by friendly crowds, he returned to Tennessee. Shortly afterwards, a restless Johnson hit the campaign trail in order to line up support for election to the U.S. Senate. Despite his best efforts, however, he lost by a close legislative vote in October 1869. Undaunted by this setback, three years later he once more campaigned for public office; he did not seem to know what else to do. This time he sought the at-large U.S. representative seat, but finished third in the contest. That defeat only whetted his appetite for new challenges, and in 1874 he launched another bid for a U.S. Senate seat. In the January 1875 legislative voting, Johnson finally emerged victorious. “Thank God for vindication” was his ardent response. When he participated in a special session of the Senate in March, he assumed the seat vacated by his longtime foe William Brownlow. At the session’s end, he returned to Greeneville, a place he had come to despise because it lacked the allure and fulfillment of the political arena. Four months later, he suffered a stroke and died on July 31. Wrapped in an American flag with his head resting on a copy of the Constitution, he was buried in Greeneville to await the judgment of history and historians.

Suggested Reading

LeRoy P. Graf, Ralph W. Haskins, and Paul H. Bergeron, eds., The Papers of Andrew Johnson, 14 vols. to date (1967- ); Peter Maslowski, Treason Must be Made Odious: Military Reconstruction and Wartime Reconstruction in Nashville, Tennessee, 1862-1865 (1978); James E. Sefton, Andrew Johnson and the Uses of Constitutional Power (1980); Hans L. Trefousse, Andrew Johnson: A Biography (1989)